Aristotle called it ‘magnificence’ – the ability to spend lavishly but well. Does this ancient idea drive billionaires to collect art?

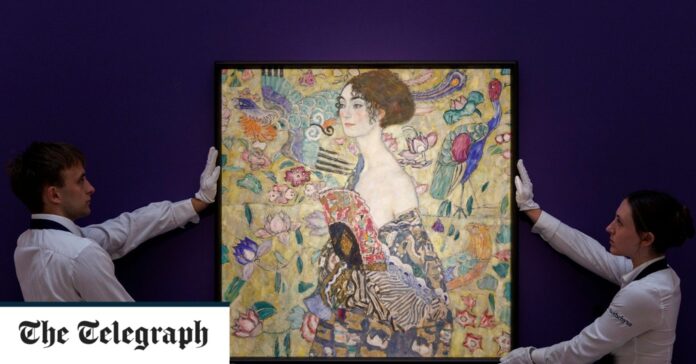

What would you buy if you had enough spare cash to afford 294 average-priced UK houses, 176 Rolls-Royce Phantoms, or a fleet of 11 Learjets? In June, an anonymous Hong Kong collector decided they had a better use for their £85.3 million and blew it all on a single artwork: Gustav Klimt’s final portrait, Lady with a Fan, painted in 1917. Inspired by Japanese woodblock prints and full of East Asian motifs, it was described by Helena Newman, the chair of Sotheby’s Europe, as “a technical tour de force, full of boundary-pushing experimentation, as well as a heartfelt ode to absolute beauty”. The sale in London smashed the record for the most expensive artwork sold at auction in Europe, previously held by a Giacometti sculpture, which sold for a paltry £65 million in 2010.

The riches that some are prepared to part with in exchange for a framed canvas, or a bronze cast, are staggering. The Frieze art fair, which takes place in Regent’s Park each year – and returns in October – is such a magnet for billionaire aesthetes that the capital’s auction houses now schedule their own big sales to coincide with it. During last year’s fair, Christie’s, Phillips and Sotheby’s together made sales totalling £165 million (and that’s alongside the millions changing hands for uber-contemporary art inside Frieze’s own tents).

For those of us who like to think aesthetic value should be unsullied by monetary value, the sums exchanging hands seem distasteful, obscene even. Yet it seems there’s no end to the madness, despite the best efforts of some to embarrass the market into greater restraint. Banksy once attempted a wry comment on the absurdity of the market, when his Girl with Balloon self-destructed in its frame after the hammer fell following a million-pound bid at Sotheby’s in 2018. But his satirical gesture merely inflated the Banksy bubble even more. Three years later, the partially-shredded piece sold for £18.6 million.

What is driving these sales? The simplest answer is that art is a secure investment. But no collector is so vulgar as to actually say that they think of art as a financial asset. They reserve that for their rivals. François Pinault, founder of the luxury goods firm Kering (the owner of such brands as Gucci, Balenciaga and Yves Saint Laurent), once claimed that big-spending hedge fund managers were artificially distorting art prices. “In part, the inflation of the art market in recent years was fuelled by what I call the new collectors who considered art primarily as an investment rather than a true passion,” he told The Art Newspaper in 2009. “Now the real collectors are back.”