David Fleming’s book Hellfire sheds light on the Hypocrites Club – where Evelyn Waugh made merry with Anthony Powell and Henry Green

The Hypocrites Club was a drinking club of Oxford undergraduates that managed to survive for three or so years in the early 1920s. Its members met in a “ramshackle building” far enough down St Aldate’s to be, as one Hypocrite put it, “somewhat outside the accepted boundaries of Oxford social life”. The clubmen’s hypocrisy consisted in their flagrant violation of their ironic motto, a line from a Pindaric ode: “Water is best.”

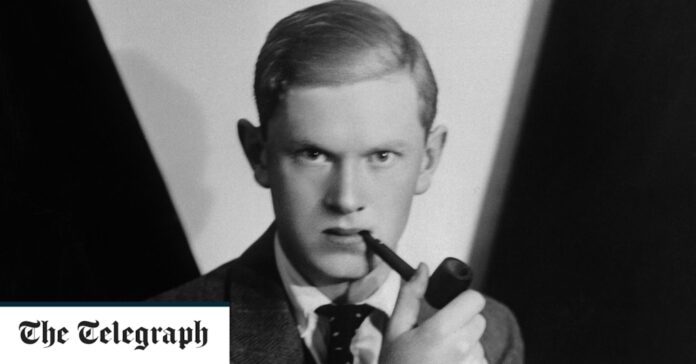

Oxford has never been short of drinking clubs. Why does one so short-lived deserve as lengthy a biography as David Fleming has given them? There is, to start with, the fact that the club counted as members three novelists of great originality (Evelyn Waugh, Henry Green and Anthony Powell) and one man with a claim to the be the 20th century’s greatest travel writer, Robert Byron. There were others – Brian Howard and Harold Acton – who never quite delivered on their early literary promise but did their bit for modern literature by providing Waugh with the inspiration for Anthony Blanche, the memorably camp aesthete from Brideshead Revisited.

But is this enough to justify revisiting that much visited literary territory yet again? Fleming proposes that the Hypocrites were special. Although they ran the political gamut from “bone-dry Conservative” (Waugh) to “firmly on the left” (the journalist Claud Cockburn), they had in common a sensibility: independent-minded, rebellious, argumentative and intolerant of cant.

Fleming begins the story of the short-lived club with an account of the cross-dressing escapade that firmed the Dean of Balliol College in his resolve to shut it down. There is a good deal of public schoolboy odiousness to get through in these early chapters. Even readers au fait with the milieu will struggle a little to forgive the Hypocrites their preposterous adolescent self-assurance as they arrive at Oxford, convinced they have nothing to learn, least of all from their tutors. The Hypocrites were seldom nice. Even those, such as Waugh, who graduated from youthful hedonism to Catholic devoutness, took little interest in what Fleming calls “the mundane side of Christian life that recommended routinely being kind to the people one met.”