Harland Miller’s canvases. increasingly gaudy and eccentrically titled, prove there needn’t be a gulf between high and low culture

His typical painting is a joke. It may resemble the cover of a Penguin paperback, adorned with the classic orange bands, yet its title will sound eccentric: Not Giving in to Will Power (2018), or Narcissist Seeks Similar (2020). Or the “cover”, bearing a Pelican over its layers of royal blue, may suggest travel to the North: such works include Grimsby – The World is Your Whelk (2006) and York – So Good They Named It Once (2020).

The long-running charge against Pop art, such as Harland Miller’s oeuvre, is that its interest in appearances is superficial and nothing more; that, bent on wealth and status, it treats intelligent viewers with disdain. Our current Prime Minister owns a Miller – Rags to Polyester: My Story (2003) – but let’s assume he’s in on the gag. If so, he’s sophisticated, for these pictures have tricksy wit. Their hues, often brooding like Rothko colour-fields, sit in a precarious balance with the titles, the humour of which is sardonic, deadpan and readily enjoyable. Don’t ask me to anatomise it, but as painted by a Yorkshireman, Armageddon – Is It Too Much to Ask? (2015) has a very Northern brand of quirk.

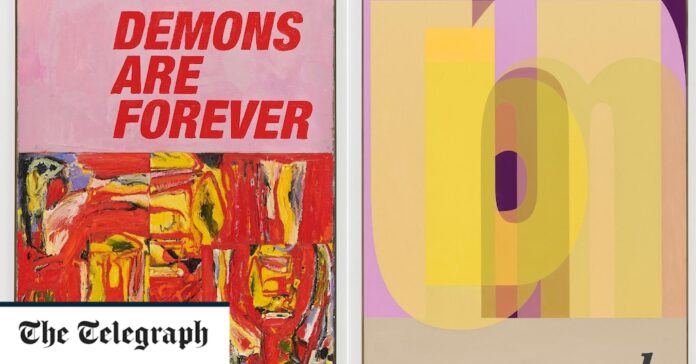

‘Imminent End, Rescheduled Eternity’, a new show of more than 40 works (all 2022) at White Cube Bermondsey, continues partly in this vein. In one gallery hang several “covers” that bear single-word titles, Miller’s name, and a graphic rendering of the titular letters, superimposed in a gaudy stack. Part of the fun lies in imagining what stories Vex or Numb might tell – flashy sci-fi? dystopian fable? drug-induced counter-cultural whine? – while another part of it, a more thoughtful kind, lies in the bizarrerie of alphabets. Anyone who has returned to the Latin script from looking at Arabic or Greek will know the jolt of seeing our letters, momentarily, as arbitrary shapes.

The largest canvases, in the rear gallery, keep the phrasal humour alive, though they’re more cerebral than Millers of yore: now we have Up as a Superposition, Define Worried, and Demons are Forever (a slack pun, unusually). Though they resemble popular-science books, we’ve quit the colour-fields: they exult in daubs and gleeful forms, their brushwork out and proud. Punning words coexist with abstraction, the immediate and the hard-to-gloss. Buttressed with those expressive marks, Miller’s humour turns pensive, elusive; the jests no longer seem to be at anyone’s expense. If these paintings advocate something, it’s that there isn’t a gulf – just the perception of one – between cultures high and low. To think that Pop art is ephemeral: now that would be a joke.