This is no time to go wobbly, as Mrs Thatcher would have said

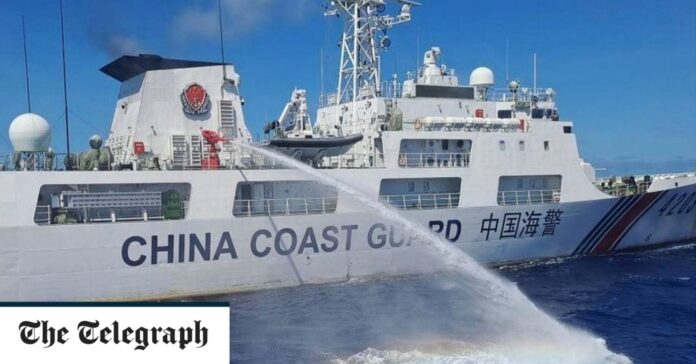

As China ups the ante across the Indo-Pacific and the Ukraine War shows signs of quagmire, calls in Washington to accelerate America’s pivot to Asia are growing. Recent clashes between Chinese and Philippine Coast Guard ships near the Second Thomas Shoal off the Spratly Islands underscore the sense of urgency. Despite the atoll falling within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone pursuant to a binding decision by an arbitral tribunal, China continues to harass Filipino civilian and military vessels in the area (showing the same contempt for the tribunal’s decision as it did for its commitments under the similarly binding Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong). The U.S. and the Philippines have a mutual defense treaty and the U.S. has reiterated its commitments under that agreement in light of these flareups, but concerns about the region turning into a powder keg are becoming harder to downplay.

In this escalating threat environment, Washington will have to make difficult strategic choices like at no time since the end of the Cold War. A mere regional pivot with a package of export controls, inbound investment restrictions against China, statements of solidarity and greater access to local partners’ bases is not enough. America must have a strategy that meets the moment to prevent China from dictating the rules of engagement or outright controlling access to the South and East China Seas.

The need to act quickly is particularly acute given growing fears about America’s defense base and ability to successfully wage or finance a two-theater war in Europe and Asia. At the same time, following much weaker than expected growth in the wake of its Covid reopening, a worsening property market and surging youth unemployment, China’s economy is showing signs of deflation. As America becomes increasingly overstretched, domestically polarized and hobbled by legacy foreign policy hangovers that prevent it from prioritizing threats and shifting gears, the Chinese Communist Party leadership under Xi Jinping will be keen to export China’s domestic deflation, deflect public attention from the country’s structural problems and more aggressively push the envelope abroad. Xi’s cultivation of a personality cult and subordination of China’s economy to the Party’s political objectives (meaning his and those of his loyalists on the Politburo Standing Committee) mark a break from the technocracy of the Deng Xiaoping era – further evidence that Beijing will be more, and not less, likely to raise tensions in the South China Sea, around Taiwan and across the Indo-Pacific more widely.

Concentrating minds on the South and East China Seas, the U.S. needs to approach China’s challenge to its interests there much like Britain approached Russia’s challenge at the end of the Nineteenth Century to the Eastern Mediterranean and British-ruled India. The South China Sea, accounting for a third of global shipping (with 60 percent of maritime trade passing through Asia), is a vital trade route for the U.S. domestic economy and global supply chain network. As Asia rises and Europe declines, this waterway should be treated as America’s own version of the Suez Canal and the prospect of its turning into a Chinese lake deemed unacceptable. Britain secured its interests in the Canal by acquiring a majority stake in the Suez Canal Company, taking over Cyprus from the Ottoman Empire, and later turning Egypt into a protectorate backed up by the Royal Navy and, at its peak, some 80,000 troops based in the Canal Zone.