In these seven eerie short stories from the author of Fever Dreams, a sense of menace is always hovering around the next corner

The title of Seven Empty Houses is a shade too definite. Throughout this septet of domestic stories, whether it’s in the homes themselves or their inhabitants’ troubled minds, the blissful calm of vacancy is still a few steps away. Instead, we read of lives on the verge of collapse: a woman obsessed with expensive houses who worms her way into one; a couple who disintegrate over the loss of a child and can’t let his belongings rest. In each case, you realise what these people have coming, and read with a mixture of pity and fear.

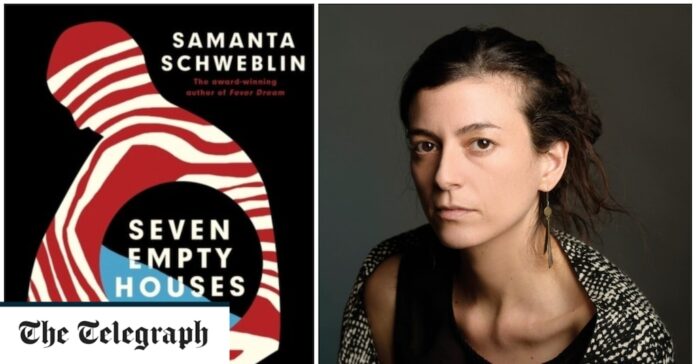

This is the third short-story collection by the Argentinian writer Samanta Schweblin, and the second to come into English via the translator Megan McDowell. Schweblin reached the International Booker shortlist with her 2014 novel Fever Dream, which mixed folk horror and eco-drama; it was an early highlight of an ongoing wave of fiction, for the most part young women’s work – see also: Julia Armfield, Oyinkan Braithwaite – that reads as both noirish and sinister, with violence broiling beneath the calm.

Seven Empty Houses prolongs that mood. Its best and longest story, “Breath from the Depths”, is concerned with a reclusive old woman, Lola, who’s aware that she’s slowly dying, and has been boxing up her life. Lacunae start to appear in telling gaps in her memory or experience. A boy from next door appears, and inveigles his way into her husband’s affections; she writes lists to pin down the world, and the world stops matching them. The boy no longer seems pleasant; there are shadows at night in the yard. The tension builds steadily, until the reveal. I expected it when it came, but that didn’t attenuate its effect.

“Breath from the Depths” sets the highest of bars, and not all its siblings attain it: some of these stories are less unsettling than unsettled, their texture imperfectly wrought. In the penultimate one, “An Unlucky Man”, an eight-year-old girl is led away by a stranger; but though this could have offered up tonal riches – childhood innocence, remembered by an adult – the style is like that of the other tales. On the other hand, the finale, “Out”, which has a comparable premise – a suffocated wife goes wandering the streets in a new man’s company – is a lesson in conjuring menace. Schweblin, at her best, has a knack for eeriness.