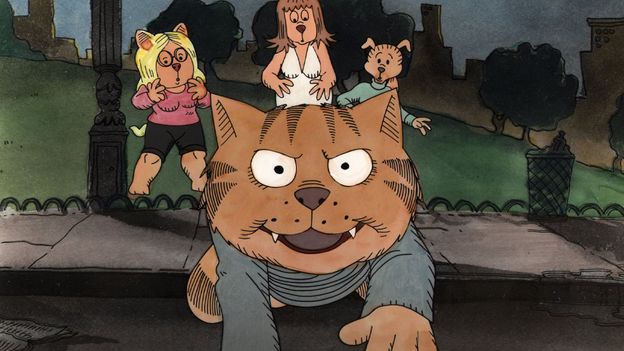

Ralph Bakshi’s bawdy and outrageous 1972 film sparked controversy when it was released 50 years ago – changing animation forever, writes Tamlin Magee.A blazer-clad student called Fritz attends drug-fuelled orgies, steals guns from corrupt cops, sets his college on fire, finds himself in the middle of a race riot, and blows up a power plant. These outrageous moments would have pushed boundaries in any number of grindhouse exploitation films, but this student was a cat, and the star of the very first X-rated animated film – decades before the likes of South Park hit our TV screens. Fritz the Cat, a bawdy 1972 rampage through New York’s underworld, is the work of Ralph Bakshi, a legendary but equally divisive cult cartoonist who has never been a stranger to controversy. More like this: – The animation too dark for Hollywood – The 10 greatest animated films for adults – Is this the worst film ever made? Using social commentary equal parts scandalous and nihilistic, Bakshi completely flipped the script on what animation could do, in a world that had until then been dominated by Disney. An adaptation of three comic books by original Fritz creator and cult comic legend Robert Crumb, Fritz the Cat’s scrappy animation contrasted its bright, lively main characters with often drab and gritty, realistic backdrops. For audiences more used to the wholesome hijinks of Mickey, Minnie, and Goofy, Fritz, which stuffed in more graphic sex scenes and bloody violence into its short run time than most live action films, came as a shock. It was a runaway success, in spite of its less-than-shoestring budget of under $1 million, and it went on to become the highest grossing independent animated film of all time. Asserting that animation could be for adults too, it was unquestionably influential in the way that it changed the industry, showing that independent animations outside of the traditional studios could be successful too. As rough and raw as it was, Fritz held up a mirror to inconvenient truths about US social issues that have never faded – fraught race relations, inequality and police brutality. Critics called it debased and pornographic; fans called it gritty and real: the jury is still out in the academic world over whether its explicit nature advanced the cause of animation for adult audiences, or hindered it. But it inarguably disrupted the animation industry, and its breakout success occurred against all odds.Fritz the Cat was created by the legendary but divisive cult cartoonist Ralph Bakshi (Credit: Alamy)What began as a depiction of Robert Crumb’s family cat Fred, Fritz eventually evolved into a self-assured beatnik who roamed (and slept) his way through the counterculture of 1960s US and the anthropomorphised “supercity” he inhabited. Crumb’s creation was part of the underground “comix” movement, the 1960s DIY illustration scene that challenged what comics and illustration could do and say. His stories had a sometimes meandering, conversational social focus that, whether the characters were animals or not, leaned closer to life in the US than the likes of Captain America. It was partly this that drew Bakshi to admire, and seek to animate, Fritz. But Crumb was reluctant to hand over the copyright. In a bargain with details that remain somewhat murky, co-producer Steve Krantz eventually produced a contract that was signed by Crumb’s wife, Dana, who held power of attorney. Crumb mostly kept his distance from the production and, on its release, was so appalled by the film that he responded by writing the very last Fritz comic, Fritz the Cat – Superstar, where the character had become a sleazy sell-out and movie star who meets with Bakshi and Krantz, before meeting his Leon Trotsky-style fate of murder by ice-pick. Copyright, though, was only the first hurdle. With his low budget, Bakshi faced substantial challenges to get the film made. The animation was produced with such scant resources that the team had to completely omit pencil testing, the early-stage storyboarding of animation that ensures quality and timing, resulting in a unique, rough-and-ready style. Unable and unwilling to pay the fees of expensive voice actors, Bakshi instead turned to real people on the streets of New York City. “I said, ‘the hell with that,'” Bakshi tells BBC Culture, about the costly fees of professionals. “‘Just get real people’. I used their voices because, first of all, it’s dirt cheap. But a lot of times I just let the recording roll, and they were talking about whatever they were talking about. I got a lot of great stuff, and it dawned on me that this was sensational. When I heard the natural sound, the traffic in the background and what they were saying, I absolutely loved it.” This ‘found sound’ technique lent the film a quasi-documentary style, and Bakshi says that jazz music was a major influence on his work owing to the “looseness” of the style – a kind of improvised approach to animation that would later appear in the Aardman Creature Comforts franchise, which animated conversations between real people.Whatever critics made of the film – and reactions were mixed – Fritz the Cat was undoubtedly gritty and real, helped along greatly by Bakshi’s choice to bring background designer and New York animator Johnny Vita on board. Rather than design whole new cityscapes from scratch, Vita travelled with his camera all around Greenwich Village and Harlem; the settings were traced over and then coloured with Luma dyes, creating an effect that’s realistic yet just slightly off-kilter, cartoonish, dreamlike – and drawn over by animator Ira Turek with the same kind of Rapidograph technical pen used by Robert Crumb, preserving his style but transported to a cartoon version of New York, making it an animated film shot “on location,” says Bakshi. Inking and painting the cells, meanwhile, caused a clash between Bakshi and New York’s animation union, which insisted on $10 a cell, leading Bakshi to contract a Mexican company and then complete the film in California, where many veteran animators were out of work. Bakshi ultimately viewed these budget constraints as a blessing: having no money forced him to innovate within the limitations that had been imposed on the film. “If you fight the budget, you sometimes come up with creative thinking that far surpasses what you would have done if you had a lot of money,” he says. “If you had money, you automatically hire the best painters, the best animators to do this and that, and the best actors. That’s what everyone else in the industry did.”Fritz the Cat held up a mirror to inconvenient truths about US social issues that have never faded – fraught race relations, inequality and police brutality (Credit: Getty Images)Neither studio heads nor distributors wanted to touch what many saw as a doomed, pornographic project, although Warner Bros eventually agreed to finance the film. But after a disastrous pre-screening where Bakshi and Krantz horrified executives with a controversial sex scene and disputes about toning down other sexual content, they pulled their money; however Fritz won funding from exploitation distributor Cinemation and the film was released. “At this time, independent production was growing, because there were certain tax incentives and the studio system itself was breaking down during the 1960s,” says animation historian and critic Maureen Furniss. “It wasn’t that unusual to have independent producers, but Ralph Bakshi was a force unto himself, he was a totally different kind of guy – and very challenging to work with.” Capturing the zeitgeist Like the US itself, the animation establishment was undergoing a period of change, and Fritz burst out from decades of censorship as well as this shift in the studio system. Antitrust legislation and the emergence of television combined to help dissolve the dominant studio system of Hollywood’s “Golden Era”. Audiences were increasingly disconnected from the “block booking” packages that the movie theatres were forced to show, where A-movies, B-movies, newsreels, and animated shorts were combined into one package. Suddenly, shorts were not viewed as profitable or desirable. So when the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cartoon studio closed in 1957, William Hanna and Joseph Barbera left to found their own studio, which began producing more rough and ready, made-for-TV cartoons in contrast to their bigger budget Tom and Jerry shorts they were making at MGM – eventually creating successes like the Flintstones. Independent, experimental films were gaining steam in the post-war period, pushing back against the censorious backdrop of moral policing and policy. The National Legion of Decency, a Catholic pressure group dedicated to identifying morally egregious films, tried to blacklist everything from Rififi (1955) to Buñuel and Rossellini, while the decades-long Hays code, created in the 1930s, clamped down on films that were sympathetic on the side of “crime, wrong-doing, evil or sin”. Eventually, in 1968, the official classification system would emerge from these kinds of groups as moral guidance; and a few years later, Fritz burst onto the scene as the first of its kind in the “X” category – bundled together with pornography, slasher flicks, and dramas like Midnight Cowboy (1969). So, while Fritz was the first X-rated animated film, the category hadn’t been around for long. “While adult content had already made its way into a number of Golden Age Hollywood cartoons of the 1930s and 1940s,” Dr Christopher Holliday, Lecturer in Liberal Arts and Visual Cultures Education at King’s College London, tells BBC Culture, “the playful eroticism of characters like Betty Boop was dialled up by the outlandish ‘rude and crude’ style of Bakshi’s animation, and particularly in his adaptation of Robert Crumb’s X-rated adult comic.”The emergence of independent, experimental, subversive films, together with changing social attitudes to young people – who started to see themselves as teenagers and students with rights – meant that Fritz the Cat arrived at exactly the right time. “Fritz is like Impressionistic painting; he let the edges show,” says Furniss. “[Bakshi] defied people to say, ‘that’s cheap’ or ‘that’s rough’. That was what he wanted. It’s gritty, and that’s what life was like, and that’s what teenagers were feeling at the time: ‘this is authentic’. So you have to look at it from a larger perspective of experimentation.” As with Crumb’s original comic strips, all the African-American characters are represented as crows in the anthropomorphised world of Fritz; a self-conscious subversion of 20th-Century depictions of characters like “Buzzy”, a short-lived Paramount character, or the infamous “Jim Crow” in Dumbo, voiced by a white actor and described as the vocal equivalent of blackface. “Bakshi hired African-Americans to voice his crows, thus rejecting his predecessors’ casting of European-Americans for African-American characters,” says Christopher P Lehman, an animation historian and professor of Ethnic Studies at St Cloud State University. “On the other hand, Bakshi’s crows replace the antebellum minstrel tropes with urban African-American stereotypes instead: the pool hall, the prostitute. Moreover, the images come from the imaginations of European-Americans, Robert Crumb and Bakshi.”Police were portrayed as pigs in the anthropomorphised world of Fritz the Cat (Credit: Alamy)But, Lehman adds, the crows of Fritz have “some progressive elements” in the context of animated African-American figures in 1972: “He developed each crow without relying on the crutch of a famous person’s distinctive voice to define the character’s personality and developed original African-American characters instead of adapting established properties to animation; after all, in 1972, The Harlem Globetrotters, The Jackson Five, and Bill Cosby’s Fat Albert were among the Saturday morning cartoons on US network television.” The use of “found sound” was novel, because US animation studios had neither recorded nor animated to the voices of African-Americans outside of the entertainment industry, Lehman adds, and unscripted conversations of African-Americans speaking in commercial US films were rare at all, let alone in cartoons.Fritz’s uncompromising attitude was “deliberately and very self-consciously offensive and its targets are everyone,” Dr Noel Brown, senior lecturer in film at Liverpool Hope University, tells BBC Culture. “The establishment (the police are pigs, literally, and we see the military gleefully blowing up Harlem), hippies, phony liberals, fake intellectuals, violent revolutionaries, hypocritical religious leaders, militant feminists, dumb workers and hicks – in this world everyone is either moronic or on the make.” A major part of its aim, appeal, and subsequent success was due to its “grotesque subversion of the Disney ethos”, says Brown. “Animation in the US was seen as being exclusively for children, and Fritz plays on the incongruity of seeing explicit sex, nudity, swearing and violence in a medium known for its innocence, sentimentality, and avoidance of any deliberate ideological positions.”Fritz was the first of its kind in the “X” category – bundled together with pornography and slasher flicks (Credit: Alamy)Under it all, Bakshi tells BBC Culture, was a 1960s underground liberal sensibility inherited from his parents, who emigrated from Haifa, then the British mandate of Palestine, to Brownsville, Brooklyn, via the USSR. Bakshi grew up in poor neighbourhoods and saw US racial segregation first-hand. So when the US Air Force bombs Harlem in Fritz the Cat, preceding the Philadelphia police bombing of black liberation group Move in 1982 by a decade, Bakshi wasn’t only lampooning race relations in the US at the time – he was foreshadowing real atrocities. “Growing up, listening to the letters coming home about people dying and what was going on in Europe, made me who I was,” he says. “In other words: life to me was very dangerous and people were not to be trusted; truth to power is very important. My films are still playing to people, because people haven’t changed – as a matter of fact, they’ve gotten worse.” Perhaps it’s this uncompromising commitment to showing the flip side of the American Dream that have helped films like Fritz the Cat, and later productions like 1973’s similarly gritty New York fable, Heavy Traffic, endure. Today, adult cartoons like Bojack Horseman and South Park are staples on TV that similarly stick two fingers up at what came before them. “But I think Fritz goes a lot further,” says Brown. “It’s much more radical in both representation and politics and was a deliberate affront to mainstream culture. It really captured the social and political zeitgeist of the early 70s – and 50 years on, it still retains its ability to surprise and shock.” Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world. If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter. And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday