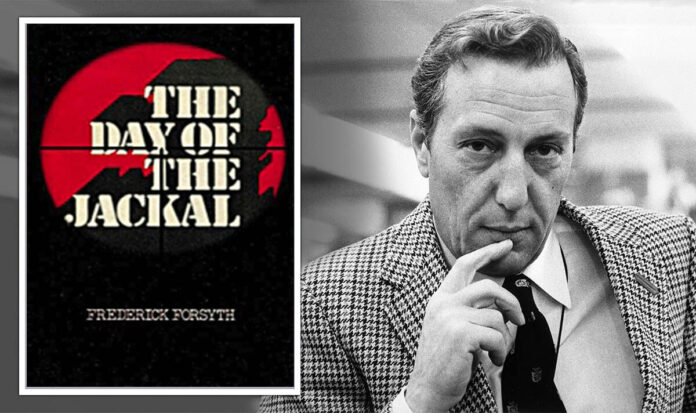

Frederick Forsyth and the novel that made him a star (Image: Getty) I was not long out of school and working on my third unpublished novel when The Day Of The Jackal came out in 1971. It was serialised in the Daily Express and I remember reading the first chapter and realising the thriller genre had changed forever. I bought the hardback, something I could rarely afford to do in those days because of the cost, and read it through to the end in several breathless sessions. Even the cover, pitch black, the title picked out in a red gunsight, was captivating. And it wasn’t just good, it was a game-changer. The best thriller I’d ever read. Freddie Forsyth had torn up the rule book and thrown it away, inventing a new form of thriller writing in the process. What he had done was incredible. Readers knew Charles de Gaulle, the former French president who had died a year earlier at 79, and the target of Freddie’s fictional assassin, had not been killed while in office. But even though we knew the killer, nameless and known only as the ‘Jackal’, couldn’t succeed, Freddie kept us gripped from first to last. You almost wanted his killer to succeed. This was the ultimate book about failure, yet a triumph of writing, pace and drama. I wasn’t alone in loving The Day Of The Jackal . It was an overnight hit, in the days before the internet and social media when an author could still single-handedly capture the imagination of the reading public, something that rarely happens today. It sold like hotcakes. But why was it so good? The answer, I think, was in Freddie’s writing. He has recalled how he treated the story as a piece of journalism. Reporting it. You could feel that utter verity in the writing, it was new and vital. And the plot was groundbreaking too, with clever twists like the assassin concealing his rifle in a crutch. And never revealing his hitman’s real identity. Freddie’s writing was so fresh. You could feel that he had been a journalist. It was the nearest thing to the French documentary film style of fictional movies, known as “cinéma vérité”, in print. Drama conveyed in a factual style of telling and all the more realistic for it. The subsequent film, in 1973 starring Edward Fox as the Jackal and Michael Lonsdale as his nemesis, the French detective Claude Lebel, was a triumph also. Fox was brilliantly cast. He was born for that role. As a writer, Freddie was on fire by now, his follow-up, The Odessa File , had been published to rave reviews and he was working on his third novel, The Dogs Of War , but the film, one of the most perfect movie adaptations ever of a book, was sensational. The Forsyth phenomenon was growing. At that time, many of the writers I admired were quite mysterious people. You didn’t really see them. They might pop up occasionally on a chat show or in the pages of a newspaper, but they didn’t really have public profiles. Freddie changed all that. He was the first rock star writer of my generation. He was out there in the African bush with the mercenaries, investigating, reporting on civil wars and strife, gathering material. Not sitting in a dusty library or – as is common now – googling the world on his laptop and never leaving his study. Freddie with Michael Caine on the set of The Fourth Protocol (Image: Lorimar) He was charismatic, good-looking and popular, he hung out with film stars. But he was also massively talented, a pioneer. Freddie launched a tidal wave of new thrillers. So many writers subsequently borrowed or took inspiration from the books and their film adaptations. The brilliance of making the gun out of a pair of crutches, the steam bath scene and the cold brutality of killing anyone in his way with hardly a flicker of emotion, let alone regret. One of my Roy Grace novels, Want You Dead , featured an obsessed lover practising with a crossbow by shooting it at a watermelon. That was a nod to the Jackal , who practised his aim on a watermelon with his sniper rifle as he prepared for the hit on de Gaulle. The book I was writing when I read The Day Of The Jackal was never published, deservedly so. Yet Freddie’s work fed into my next novel, Dead Letter Drop , a spy thriller that became my first published work in 1981. Though it didn’t enjoy the same overnight success as the Jackal , I owe a debt to Freddie for the subsequent success I’ve been fortunate enough to enjoy with my books. Almost every writer I’ve ever met can name one or two books they finished and felt a beat of excitement in their heart. It struck me when I read Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock , it happened with The Day Of The Jackal , and it happened again when I read The Silence Of The Lambs by Thomas Harris. Each time, I thought: “I want to be able to write like this.” Before Covid, I was on the board of ThrillerFest in New York, a conference for writers and fans of crime fiction, mysteries and the thriller genre. Asked who I’d like to honour as a master of the trade, I picked Freddie, of course. He was due to come to New York to be honoured but then Covid got in the way so we’ve never met. I still hope we will one day, but until then, as he retires from his weekly Daily Express column, thank you Freddie, for all you’ve done for readers and writers. ● Peter James’ latest Roy Grace novel, Stop Them Dead, (Macmillan, £22) is published on September 28. To pre-order, visit expressbookshop.co.uk or call 020 3176 3832.