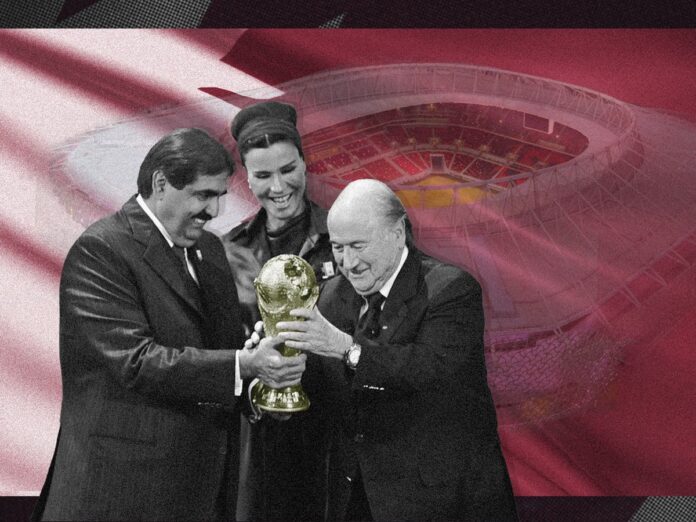

Out of the many facts and figures circulated about Qatar’s problems, there is one realisation that should stand above everything. It is a disgrace that, in 2022, a country can host a World Cup where it has lured millions of people from the poorest countries on earth – often under false pretences – and then forced them into what many call ‘modern slavery’. And yet this has just been accepted. The World Cup carries on, an end product of a structure that is at once Orwellian and Kafkaesque. A huge underclass of people work in an autocratic surveillance state, amid an interconnected network of issues that make it almost impossible to escape. ‘It’s all so embedded,’ says Michael Page of Human Rights Watch. Many will point to similar problems in the west but this isn’t the failure of a system. It is the system, global inequality taken to an extreme. ‘The bottom line is that these human rights abuses are not normal for a World Cup host,’ says Minky Worden, also of Human Rights Watch.Qatar 2022 has so many concerns it has a strong claim to be the most problematic football competition ever, maybe surpassing Argentina 1978. It is so bad that, when human rights groups went to federations with various individual points, they were told to come up with common causes.That led to the call for Fifa to match prize money with compensation for migrant workers, but there hasn’t yet been movement on that. One simple appeal to humanity hasn’t yet moved the game. That makes it all the more relevant to actually spell out everything the world is walking into. You can jump to any of the following sections, below: When Qatar shocked the planet by winning the World Cup bid in December 2010, it was ‘probably the Gulf state about which the least was known’, according to FairSquare’s Nick McGeehan. That has drastically changed.Qatar went for the competition to drive an economic diversification programme for a world after fossil fuels, and key to that is presenting the country as a business centre without complicated questions on human rights. It is the most elementary example of ‘sportswashing’.’It was done in 1936,’ Page says, ‘but it’s now supercharged.’ It’s also far more sophisticated than simple image improvement. It is really about buying off or integrating into western infrastructure so moral scrutiny becomes impossible. Qatar has similarly invested billions into EU countries, completely subduing the usual political criticism. It is how this World Cup can somehow be held without significant reform.’As we’ve seen with Saudi Arabia, nations with deep pockets and poor human rights records are undoubtedly aware of how sport has the potential to reshape their international reputation,’ says Sacha Deshmukh, Amnesty International’s UK chief executive. ‘This is the modern playbook. The calculation appears to be that a new investment in sport may bring some temporary criticism, but that this will be outweighed in the longer term by the substantial rebranding benefits.’In that sense, this World Cup will ensure Qatar is associated with modern equivalents of, say, Gordon Banks’s save against Brazil. It is a powerful thing. As one source argues, ‘it’s a lot harder to invade somewhere if they’ve just hosted a World Cup’.This is where reference to Saudi Arabia is so pointed. The bid for the World Cup came amid an escalating regional rivalry that led to the 2017 Gulf blockade, Qatar on one side, United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia on the other. And what is happening on Sunday? It was supposed to just be the Abu Dhabi Grand Prix. Instead, the World Cup’s opening game has been moved, overshadowing everything and underlining what sport has been reduced to.The reasons that Qatar shocked the world in 2010 was because they didn’t seem to have support or even infrastructure, given Fifa’s own report described their bid as ‘high risk’. They did have a lot of money, though. Whistleblower Phaeda Almajid has since claimed she was in the rooms as members of Fifa’s executive committee were offered bribes of $1.5m. It has similarly been reported by the Sunday Times that Mohamed bin Hammam, the driver of Qatar’s bid, had used secret slush funds to make payments to senior officials totalling £3.8m. Bin Hammam was banned for life from all Fifa related activities by the ethics committee, although this was later overturned due to lack of evidence, but then reinstated over conflicts of interest.In April 2020, the United States Department of Justice alleged that three exco members received payments to support Qatar. The FBI’s William F Sweeney Jnr stated how ‘the defendants and their co-conspirators corrupted the governance and business of international soccer with bribes and kickbacks, and engaged in criminal fraudulent schemes’.The Supreme Committee has long denied the claims.If there’s one issue that has most dominated coverage of Qatar, and especially angered the state, it is the report of 6,500 migrant worker deaths first set by The Guardian. That anger, to be blunt, is itself an outrage.The only reason Qatar can possibly dispute the figures is because of the circular tragic farce that the state simply won’t investigate deaths. ‘This is the scandal of it,’ McGeehan says. ‘It’s the wrong argument. It’s about the proven negligence and the rate of unexplained deaths.”That, according to a 2021 Amnesty International report, stands at approximately 70 per cent. What can be said with absolute certainty is that the actual number would be shocking, although even the three deaths officially recorded – Zac Cox, Anil Human Pasman and Tej Narayan Tharu – is obviously tragically bad enough. It goes without saying that a sporting competition should not involve a single death or any human suffering.And yet Qatar has involved numbers that, statistically, are likely to be magnitudes higher. Hundreds of thousands of workers have been for years forced to work in searing summer months, which FairSquare describes as a ‘demonstrable risk’ to workers’ lives due to ‘clear evidence linking heat to worker deaths’, especially when allied to strenuous work.A report Qatar itself commissioned found workers are ‘potentially performing their job under significant occupational heat stress’ for a third of the year. One in three workers were found to have become hypothermic at some point.The country’s list of ‘occupational diseases’ does not include deaths resulting from heat stress.Instead, Amnesty’s study claims that approximately 70 per cent of migrant worker deaths are reported with terms such as ‘natural causes’ or ‘cardiac arrest’.’These are phrases that should not be included on a death certificate,’ pathologist Dr David Bailey told Amnesty. Those phrases also mean they do not get recorded as deaths linked to the World Cup, and neither do those outside the ‘footprint’ of the stadium. Additionally, Qatar has historically prohibited post-mortems, unless to determine a criminal act or pre-existing illness. ‘They have not investigated circumstances where a worker dies in their bed,’ Page adds.A recent Daily Mail investigation claims that, between 2011 and 2020, 2,823 foreigners of working age died of ‘unclassified’ reasons. The International Labour Organisation [ILO] have meanwhile noted there is likely under-reporting, because companies want to avoid reputation damage or paying compensation, which starts to cut to the core of the problem.’They haven’t been pushed on it enough,’ Page says ‘I think there are two factors around the lack of meaningful independent investigation. One, it wouldn’t make them look good. Two, being on the hook for compensation. We’ve tried to be cautious at HRW, we’ve said thousands, but we don’t know precisely because of the Qatari authorities. It’s all the more frustrating because their health infrastructure has the capacity to measure this.’But they don’t want to make data knowable that highlights what the severity of the problem is.’One of the sad ironies of this tournament is that it is supposed to be Qatar welcoming the world, in the global party the competition has become, but a lot of the world just doesn’t feel welcome.’We’re not travelling to this World Cup,’ says Di Cunningham of Three Lions Pride. ‘That’s in spite of the fact we travelled to Russia. There is a toxic environment for LGBTQ and other minority groups.’Article 296 of Qatar’s penal code specifies that same-sex relations between men is an offence, with a punishment of up to three years in prison. The death penalty is possible under sharia law, but there are no known records of it being enforced for homosexuality. Qatar has continued to insist everyday reality is different and everyone is welcome so long as they respect the culture, but this just isn’t sufficient for LGBTQ groups.’We’re hearing what seems to be this kind of robotic insistence that all will be well, that we’ll be safe, that we’ll be welcome,’ Cunningham says. ‘But there’s been no documented plans, no unified messaging, no apparent collective will. It’s actually been the opposition. We’ve seen unchallenged public demonising of LGBTQ people from prominent members of the establishment.’The week before the World Cup saw the latest in a series of alarming statements, with former Qatari international Khalid Salman describing homosexuality as ‘damage in the mind’. It feeds into a culture that has seen Human Rights Watch report that the Qatar Preventive Security Department forces have arbitrarily arrested LGBTQ people and subjected them to ill-treatment, with six cases of severe and repeated beatings and five cases of sexual harassment in police custody between 2019 and 2022. Transgender women had their phones illegally searched, and then had to attend conversion therapy sessions as a requirement of their release.These acts could constitute arbitrary detention under international human rights law. One transgender woman reported that an officer hit and kicked here while stating ‘you gays are immoral, so we will be the same to you’.Another described the Preventive Security as ‘a mafia’ who beat her every day and shaved her hair, while making her take off her shirt to take pictures of her breasts.’It’s a situation where people of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities are unfortunately unable to live their lives openly,’ says Chamindraw Weerawardhana of ILGA World (the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association). ‘Fear of the establishment prevails. These basic rights we’re talking about are fully compatible with Islamic principles of human rights.’Thomas Beattie, a former professional footballer who came out in 2020, echoes such sentiments. ‘Awarding the privilege of hosting a global foreign event to nations which embody this mindset is really damaging to my community, especially because you kind of send this message that we’re a secondary thought and we don’t really matter,’ he says. ‘I don’t think I would feel any safer.’One of many poignant scenes in a documentary called The Workers Cup is when Kenneth, from Ghana, talks of when he was first lured to Qatar. A recruitment agent made the 21-year-old think he would be transferred from a construction job to a professional football club. That didn’t happen.It should be acknowledged that most workers come of their own accord, since a meagre salary in Doha can be transformative in Nepal or Bangladesh. That’s also where the exploitation starts.There’s a haunting line from another migrant in the documentary, Padam from Nepal.’When I discovered the reality it was too late.’That reality, according to Isobel Archer of the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC), involves illegal recruitment fees amounting to ‘hundreds, or even thousands of dollars and is one of the worst drivers of abuse in the region’. It has been estimated that Bangladeshi men have paid £1.14bn in fees between 2011 and 2020.Since most workers can’t afford this, and need to arrange loans or wage levies, it instantly puts them in debt and, essentially, a financial trap. Their general salary is between $220-350 a month, meaning they can never make enough to free the debt and ‘leaving them vulnerable to a range of exploitative practices,’ according to Michael Posner, director of the NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights.’Since 2016, we have recorded xx cases of migrant workers paying recruitment fees in Qatar,’ Archer adds. ‘Undoubtedly there are workers looking after football fans and teams this month who toil under the burden of debt.’Although Qatari authorities have stated the practice of recruitment fees is outside their jurisdiction, Human Rights Watch has said they have failed to address the role Qatar-based businesses play in passing on costs to recruiters they know will be borne by workers, and that there is insufficient oversight.This is the gateway to so much abuse.In a recent Amnesty report on security workers, many interviewers said they couldn’t remember their last day off, with over 85 per cent saying those days were usually up to 12 hours long. Yet, when one interviewee claimed he tried to take a sick day, he was told he would be docked wages and felt in fear of deportation.’You are like a programmed computer; you just get used to it. You feel it is normal, but it’s not really normal.’Denying employees their right to rest through the threat of financial penalty, or compelling them to work when ill, can amount to forced labour under the ILO Convention on Forced Labour. This is one of many descriptions around Qatar that just shouldn’t be used in 2022, let alone for a football tournament.Professor Tendayi Achiume, the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, described ‘indentured or coercive labour conditions’ that recall ‘the historical reliance on enslav

20 September, Friday, 2024