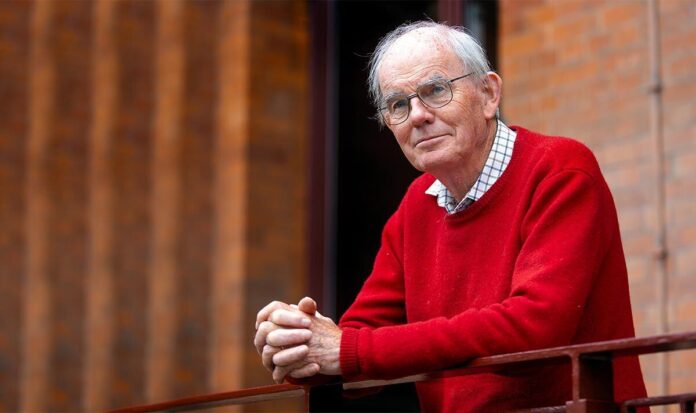

Former Labour MP Chris Mullin He never attained Cabinet rank or held one of the great offices of state. He was no mesmerising orator like his ally Tony Benn or an electoral colossus like Tony Blair. Earnest, bespectacled and slightly diffident, he did not exude charisma or project power. Yet the name Chris Mullin will be cherished by historians long after most of his contemporaries have been long forgotten. That is because of the revealing diaries he has kept over recent decades, providing a unique record of our times. A junior minister in the last Labour government and a northern MP for 23 years, Mullin had a ringside seat at Westminster. But his political career and personal story might well have gone in another direction had it not been for the fickle hand of fate, as he reflected when we met at a London hotel to talk about the latest instalment of his diaries which have just been published. Chris Mullin talks to our Leo McKinstry Fixing me with an amused smile, he says: ‘It seemed like a setback at the time, but, in fact, it was one of the best things that ever happened to me.’ We had been discussing Labour personalities when I mentioned that, before I became a writer, I had worked for Harriet Harman, below, whose Parliamentary career began when she won a by-election at Peckham in 1982. Mullin has powerful memories of that contest because he had almost beaten her in the battle to win selection as the Labour candidate. Well-known in Left-wing circles as an activist and journalist, he had just fallen short by three votes. At the time he was crestfallen. Yet there followed a highly productive period that brought him far more acclaim, controversy and influence than he could ever have achieved as the new MP for Peckham. Chris Mullin almost became MP for Harriet Harman’s seat of Peckham Out of Parliament in 1982, he enjoyed enormous success with his novel, A Very British Coup, whose compelling plot featured a radical Labour Prime Minister overthrown by the secretive establishment. Further fame came from his heroic mission to highlight the miscarriages of justice in the cases of those wrongly convicted of IRA bombings in Birmingham and Guildford. Within five years, he had been elected for Sunderland South, which led him to settle in Northumberland with his Vietnamese wife Ngoc. He met her while working in the Far East, another experience that would have been denied to him if he had been the Peckham selection. ‘My whole life could have been very different,’ he tells me. Despite having left the Commons in 2010, there is no sign that he is going into a quiet retirement. Indeed, Tony Benn famously said that he stopped being an MP so he could spend ‘more time on politics’. In the same vein, Mullin remains formidably busy, from sitting on public committees to speaking at literary events and writing. Alan Clark adored Mrs Thatcher SUBSCRIBE Invalid email We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info ‘The political meeting is not dead, as some claim. It has just been transferred to the literary festival circuit,’ he tells me. At the centre of the interest he still attracts are his published diaries. Shrewd in his insights, elegant in his style, and waspish in his judgments, he has rightly been described as the Labour equivalent of the late Alan Clark, the maverick Conservative grandee whose diaries form one of the richest accounts of Margaret Thatcher’s rise and fall. The brilliance of Clark’s diaries lies not just in his gripping insider descriptions of the plotting and poisonous feuds at the top of the Tory party, but also in his lacerating honesty about his colleagues, his worship of Mrs Thatcher and his own spectacular foibles, especially his obsessive serial adultery. Mullin does not have that kind of spice. Tony Benn was a Labour MP and a prolific diarist But he has his own appealing assets, among them a wonderful sense of the absurd, a spirit of amused detachment, and a novelist’s gift of narrative. That is why he is fit to be bracketed with Clark. Three previous volumes, each dealing with a five-year period up to 2010, came out between 2009 and 2011. Now this new book, Didn’t You Use To Be Chris Mullin?, covers a dozen years from the formation of the Tory-led Coalition. Although he is out of Parliament, his commentaries remain as enjoyable as ever, enriched by their humour and humanity. The unprecedented political upheaval provides him with plenty of material, including Brexit, which he strongly opposed, the threat of aggressive identity politics to freedom, and the advent of Covid. ‘Every day our little world grows smaller,’ he writes in mid-March 2020. At times he can be deeply moving, as in his description of ‘the dignified, beautifully understated’ funeral for Prince Philip, where the Queen, ‘a tiny, hunched figure in black’ said a final goodbye to her husband of 73 years, ‘knowing that she will be shortly following him into the Great Silence that awaits us all’. But he despises those other royals, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex, ‘parading their victimhood’ on TV. ‘How long before the marriage ends and Harry comes limping home in tears,’ he wonders. I tell Mullin that Harriet Harman always admired his integrity, recognising, in particular, the courage it took to campaign for justice over the wrongly convicted IRA bombers. Indeed, in his diary, he quotes some of the chilling abuse he still receives: ‘mongrel terrorist appeaser, gutless bastard, corrupt and depraved protector of murderers,’ ran one message. His sense of ethics meant that he always refused to name his sources at the heart of his campaign, even at the risk of going to prison, while, tellingly, during the Westminster expenses scandal, he had emerged as one of the lowest claimants. Nor does he peddle salacious gossip in his diaries, though, in reference to the Westminster sex pest scandal, he relates a tale of how he was stalked by an infatuated woman from the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy. On one occasion she turned up at his flat, claiming to have missed the last bus home, so he led her ‘with the minimum of ceremony’ to the spare bedroom. During the night, however, she ‘barged’ into his room several times, then left the next morning after she ‘sprayed the inside of my shoes with scent’. Later, she sent Mullin a number of obscene letters and went in pursuit of the gay Labour MP Chris Smith, ‘who she decided looked like me’. For a Left-winger, Mullin is refreshingly free of partisanship, which makes his character studies all the more interesting. One poignant scene occurs in 2014 when his great friend Tony Benn, almost on his deathbed, tells him: ‘My life has been a failure.’ It is a verdict Mullin tried to contradict. Informing me that he admired the ‘decency, authenticity and courtesy’ of Jeremy Corbyn, Mullin adds that he would have been ‘a perfectly hopeless Prime Minister’. In his diaries, he is also scathing about Gordon Brown’s ‘personal inadequacies’ including ‘the volcanic rages, the chronic indecision, the desperate, backfiring gimmicks and the inability to engage with all but a handful of colleagues’. In contrast, he admires Tony Blair, whom he calls ‘The Man’, despite his own opposition to Iraq. He also thought George Osborne was a kind of strategic ‘genius’ though he loathed the former Chancellor’s austerity policies. An earlier opposition politician he admired much more was the Liberal Leader Jeremy Thorpe, whose North Devon seat he fought in 1970. ‘I rather liked him. He was not just flamboyant. He could really galvanise the constituency,’ he recalled. Mullin was in Devon then because his journalistic ambitions had won him a place on the Daily Mirror journalism training scheme, based in the county. ‘We were constantly told that, if we worked really hard, we might get a paragraph in the Mirror,’ recalled Mullin. So his colleagues were both annoyed and surprised when he managed to get a two-page spread in the paper based on an interview he had conducted with the Prime Minister Harold Wilson for Student magazine, run by a young entrepreneur called Richard Branson. ‘I had 40 minutes with him and he was very genial. I asked what was his biggest mistake and he said that it was to underestimate the power of speculators on the value of the pound.’ Trending With remarkable self-confidence, he turned down the subsequent job offer from the Mirror because he wanted to travel in Asia as a freelance journalist. Despite some big commissions, it was a tough existence. ‘I was mainly living on fresh air and holy water,’ he recalls. His fortunes changed dramatically with A Very British Coup, which he wrote with astonishing speed over just 30 days, taking just seven days over the last third, his urgency driven by the knowledge that fellow Left-wingers were also working on drafts with similar plots. His book was such a triumph that it was twice made into a TV drama and was recently given a boost by the Corbyn saga. He recently wrote a sequel, The Friends Of Harry Perkins. But an even bigger industry has developed around his diaries, which were turned into a West End play a few years ago and have twice been a BBC Book of the Week.

Chris Mullin: The greatest diarist since Alan Clark is back with another volume

Sourceexpress.co.uk

RELATED ARTICLES