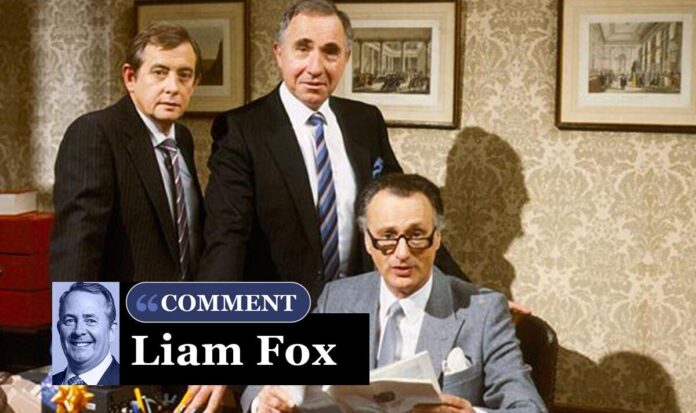

The TV series satirised state policies being thwarted by civil servantsvil servants (Image: BBC) The Sue Gray scandal has brought Civil Service impartiality into sharp focus. One of the most senior civil servants trusted with the sensitive internal workings of a Conservative government jumped ship to work as the closest aide to the Labour Leader of the Opposition. A damning official Cabinet Office inquiry found she breached impartiality rules and could have been sacked had she not quit. Meanwhile, asylum approval rates are 72 percent, despite ministers making it clear there should be rigorous application of the rules. France, by comparison, has a 25 percent success rate. Home Office Civil Service union members openly oppose the Government’s immigration plans and now former department chief Emma Haddad will take up a post at Amnesty International, which called Rishi Sunak’s Migrant Act ‘inhumane, racist and divisive’. Stories are legion across Whitehall about the resistance put up to thwart the democratic decision to leave the EU. Allegations of bullying have, for some reason, been focused on ministers most associated with Brexit and pursuing some of the most controversial government policies. Cumulatively, all of this has harmed the relationship between ministers and civil servants. The fact the law requires civil servants to ‘carry out their duties for the assistance of the administration whatever its political complexion’ suggests it is not working properly and needs to be changed. Can you imagine working in a company where the CEO couldn’t sack the finance officer? That is the position in government. The Permanent Secretary is technically the accounting officer but cannot be dismissed by the Secretary of State. That single change would ensure the top civil servant in each department was fully responsible for delivering government priorities. But change now needs to go further. Most countries have a mix of political advisers who move in and out of government, supplemented by a permanent civil service. I am not suggesting moving to the extremes of an American system, where government doesn’t fully function for long periods following a change of administration. But there are a number of European and Commonwealth countries from whom we could learn a lot. Sue Gray in civil service scandal (Image: Getty) A change to a US system is too far removed from what we have traditionally had and would amount to revolution, not evolution. But Canada, Australia and Germany have systems where, to varying degrees, there is political control over the top jobs. This hybrid between the ‘winner takes all’ approach, and the non-partisan model on which the Civil Service is based, could be a template for us. It would produce much cleaner distinctions between the political and the genuinely impartial and it needs to be policed by new mechanisms established under a new Civil Service Act. When Theresa May asked me to establish the Department for International Trade after the Brexit referendum, it was clear we did not have the necessary skills to create an independent policy entirely from within the Civil Service. Luckily, we could draw on the expertise of strategic partners such as Canada, Australia and New Zealand. They advised us, for example, on establishing our own trade remedies function. Yet, when we tried to extend the principle of sharing skills with the private sector, allowing civil servants to spend time in real businesses and business people to spend time learning about how the department works, we faced complete institutional resistance. Such an attitude means the most senior advisers to ministers are the ones who have been the longest away from their own areas of expertise or the wealth-generating parts of the economy. Many leaders have toyed with reform but have regarded it as too time consuming or too low a priority. This has meant meaningful change has constantly been ducked. That needs to end. The Conservatives must be willing to be radical with Civil Service reform in the next manifesto. With a mandate, the Government would be more able to deal with the inevitable resistance to change, including from the House of Lords. The ability to use the Parliament Act, if necessary, to enforce the will of the elected government needs to be thought about in advance. Finally, we should remember the most important point of all. The Government, through Parliament, is there to carry out the instructions it receives from the electorate at a general election. Nobody in a democracy should have the arrogance or the ability to put their own views ahead of the voice of the British people.

Britain’s civil service chiefs are sabotaging elected ministers, says Liam Fox

Sourceexpress.co.uk

RELATED ARTICLES