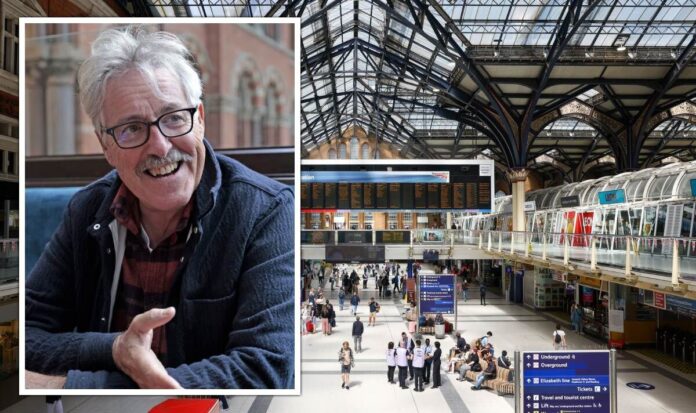

Griff Rhys Jones is president of The Victorian Society (Image: GETTY/JONATHAN BUCKMASTER)It prompted a lifelong respect for the works of the journalist, writer, broadcaster, poet and urban conservationist who, following his knighthood, was made Poet Laureate 50 years ago this month. Back then, he could not have known that he would one day follow in Betjeman’s footsteps, not so much as a poet but by becoming president of The Victorian Society, a charity founded by Betjeman to preserve the architecture he so adored. But today, Griff and the society are fighting to protect one of the UK’s most important Victorian stations, London’s Liverpool Street, a cause close to Betjeman’s heart.Plans have been announced by Network Rail to redevelop Liverpool Street with a 20-storey tower block comprising a new hotel and offices. If they go ahead, it could mean obliterating the view of the sky through the vast glass roof of the station that dates back to 1874.It is feared the redevelopment would also destroy the conservation-led scheme created after the station was saved the first time round by Betjeman and The Victorian Society back in 1975.Victorian railway buildings and churches were a particular passion for the poet. And Griff’s interests also go beyond just architecture to the towering achievements of a period in our history he believes has become unfairly maligned.He laments the current trend to view the entire era in negative terms because of the actions of a small percentage of Victorians, such as those who profited from colonialism.”It’s become rather fashionable in this country to dismiss the past as just a series of evil oppressions,” explains the energetic 68-year-old.”But I genuinely feel the Victorian era was also the era when Britain led the world with child labour legislation and factory acts – such as reducing work hours and providing education for young people.”It led the world by bringing in compulsory bank holidays and the idea that staff should have statutory annual holiday entitlement – and that led, in turn, to some of the most beautiful seaside architecture in the world. It was actually an era of great care.” Liverpool Street station in the 1930s (Image: GETTY)Betjeman cared passionately too about how people treat each other and expressed it perhaps most pertinently in arguably his most famous lines: “Come friendly bombs and fall on Slough! It isn’t fit for humans now…”In it, Betjeman rants not at the buildings or people of Slough itself but at a mindset. The poem’s darker tones, which rail bitterly against the greed, chauvinism and casual misogyny that was a regular feature of the 70s workplace, are brought out in the last verses as he calls for the bombs to rain down, “And get that man with double chin. Who’ll always cheat and always win. Who washes his repulsive skin. In women’s tears.”Often, though, he used his poetry and prose writing to make us look again at this country’s neglected heritage, especially its Victorian architecture. By doing so, he made us care once more for the many beautiful but unloved buildings all around the country and do something to save them from decay and demolition or, worse as he saw it, “modernisation”.He told Roy Plomley, who interviewed him in 1975 for the BBC’s Desert Island Discs: “When people? pull down things you’ve known all your life, they’re hacking away part of your soul.” Griff with the 8.5ft bronze statue of Sir John Betjeman at St Pancras (Image: Jonathan Buckmaster)He saw churches and railway stations as more than just places for praising God (Betjeman was an active member of his own church) or waiting for his favourite mode of transport: trains (he hated cars but realised he needed them sometimes to visit the more rural places he loved, such as Trebetherick in Cornwall where he was buried in 1984).He appreciated and valued churches as important stores of British history, from which you could learn so much about, and feel a connection with, the people who had lived in a place before you. He felt similarly about railway stations. In his recent book A Passion For Places, former Archdeacon of London David Meara, describes howBetjeman saw Britain’s major railway stations – Temple Meads, Bristol; King’s Cross, London; Newcastle Central, and, of course, Liverpool Street and St Pancras in London – as being like cathedrals.He quotes the poet: “The study of railway stations is something like the study of churches? for transepts, read waiting rooms; for hangings, read tin advertisements.” Sir John Betjeman saved St Pancras Station in 1967, just ten days before demolition (Image: GETTY)Indeed, two of the most famous buildings Betjeman helped rescue were railway stations: Liverpool Street and St Pancras.He campaigned to obtain Grade I listed status for the latter and succeeded just ten days before the wrecking ball was due in 1967. These days, St Pancras serves as the London terminus for international Eurostar services as well as housing a spectacular five-star hotel – designed by George Gilbert Scott – and a pub and restaurant named The Betjeman Arms in honour of the building’s saviour.It’s the only place you can eat a Betjeman Burger whilst admiring an 8.5ft bronze statue of the poet on the concourse.The Betjeman Arms is the perfect place to meet Griff. The actor and comedian found time to talk with the Daily Express in between filming a David Walliams children’s film for the BBC and finishing the last few dates of his comedy tour.”I think railway of London some of glories, its Despite the former Not The Nine O’Clock News star’s successful career and razor-sharp wit, his manner is both easy-going and self-deprecating.”I used to be a tour de force, now I’m forced to tour,” he jokes as we sip mineral water on the terrace.After discussing Betjeman’s poetry, which Griff lovingly describes as like “frozen emotion”, we move on to the threats to England’s Victorian heritage – as urgent now as they were in the former Poet Laureate’s time.He explains: “I became aware when I first got involved in conservation that there’s a great tradition of people picking up where John Betjeman started and that I was following in very revered footsteps.”Towns and cities the stations are its real they’re palaces’ are the great repositories of really amazing experiences for human beings. And we have to be cautious that they don’t fall into dereliction.”This station we’re in right now – St Pancras – is, like Liverpool Street, a monument to an age and an era which we should be careful to accept as part of our heritage and part of our story.”After his first conservation campaign, which helped save the Victorian Hackney Empire theatre in East London, then presenting BBC TV series Restoration and a 2006 BBC tribute entitled Betjeman and Me, Griff admits going “through an experience which taught me quite a lot about the actual fight involved in conservation”.He continues: “I don’t think of myself as the heir of Betjeman in terms of his detailed and incredible knowledge and love and authority of Victorian architecture.”I can’t compete with that. But I am an authority on the ideas and ambitions of conservation.” And help is needed now in the case of Liverpool Street station.”What has set an enormous number of heritage bodies on alert is that this redevelopment is being presented as a fait accompli,” says Griff. “It’s being presented without consulting any of the statutory bodies properly, in particularly The Victorian Society, which was responsible for saving Liverpool Street station from oblivion back in 1975.”Griff agrees with Betjeman’s view on Victorian railway architecture: “I think the railway stations of London are some of its real glories, they’re its palaces.”Indeed Betjeman’s love of trains is something else that Griff shares, despite he and his brother having had to share their childhood with an oversized model railway set. “My father loved his giant railway set and the only place he could put it was in our bedroom. It should have put me off them but I’m just somebody who loves railways,” he smiles.”If I’m going anywhere and they say, ”We’ll send a car’, I always ask, ‘Can I go by train?’ There’s something about a train which I think is rather poetic.”Now, as president of The Victorian Society, he is building up a head of steam to encourage and educate others to be as concerned as he is by threats to Britain’s Victorian heritage, whether they be to largescale infrastructure like Liverpool Street, or smaller buildings closer to home.He says: “There may be a church on the corner of your street or an old Victorian pub. And the question you or the community has to ask is, ‘Wouldn’t you rather have that church or pub there, rather than a couple of really shoddily made new buildings on the site?'”And because those are things that help give our town or city an identity, most people would say ‘I’d rather have the church? or the pub!'”A Passion For Places: England Through The Eyes Of John Betjeman by David Meara (Amberley Books, £14.99) is out now. For more information on The Victorian Society and its campaigns, visit victoriansociety.org.uk

Comedy legend Griff Rhys Jones is fighting to save Britain’s Victorian

Sourceexpress.co.uk

RELATED ARTICLES