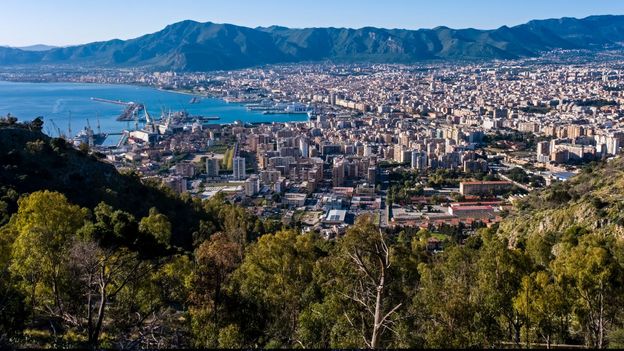

How should the state protect children raised in organised crime families? Italian courts are tackling this thorny issue. Claudia Caramanna has only been in her role two years and her work is already attracting unwanted attention. A year ago, an anonymous letter with a hand-drawn cross on it was sent to her home. Then, in March this year, a group of thugs broke into her office at night and turned the place upside down. For her own protection, Caramanna has now been given a police escort. She took up her role as public prosecutor for the juvenile court of Palermo in July 2021. Many of her investigations have focused on the children of Mafia bosses and drug traffickers. In some cases, she has asked for them to be removed from their families and placed in a care home. These interventions have turned Caramanna into a target by enraged Mafia clans. But according to her, separating children from their criminal parents is sometimes the only way of keeping them safe. “We don’t take this decision lightly,” Caramanna tells the BBC in her office in Palermo. “On the contrary – it’s the very last solution, when there are no others.” Caramanna’s work in Sicily is one more attempt to protect children from being dragged into the dangers of organised crime. It joins the Liberi di Scegliere (Free to Choose) project in the Calabria region, which started in 2012 and was the subject of the film Sons of ‘Ndrangheta, released in 2019. Only a relatively small number of children and teenagers have been removed as part of these programmes – about 80 underage persons and 30 family units in Calabria since 2012. But the projects have sparked a wider discussion over the wellbeing of children in Mafia families – and what the state should do to help them. Some critics worry that the trauma of living apart from their families will be worse than the risks of remaining where they are. “The public opinion is quite divided,” says Ombretta Ingrascì, a researcher at the University of Milan who specialises in the sociology of organised crime families. Even in Palermo, where people are well aware of the danger of growing up in the Mafia, some believe that the family unit should be preserved at all costs. Caramanna was especially surprised to be publicly criticised by a local priest in Palermo, who made it quite clear that he considered a child’s place to be with their mother and father. “I wanted to speak to him in person,” says Caramanna, “to explain that it isn’t a form of punishment.” She emphasises that children are not removed without good reason: “I will never get tired of saying that it only happens in unavoidable situations, such as when a parent is a drug dealer, and the child becomes involved [in the crime].” “The Wall of Legality” in Palermo, with portraits of people who died in the fight against the mafia (Credit: Getty Images) Growing up in the Mafia What’s commonly referred to as “the Mafia” actually covers many different clans in Italy – the most notorious of which are the ‘Ndrangheta in Calabria, Camorra in Campania and Cosa Nostra in Sicily. Growing up in these organisations shapes children’s lives from the start. “There is a myth that the Mafia does not involve women or children, but it’s not like this,” says Franco Nicastro, a journalist in Sicily who has written about Mafia culture for decades. “Children are prepared for a criminal life; it’s part of their upbringing.” Both parents may, for example, educate the children about Mafia culture and its values, such as omertà (a code of silence, meaning, one must not speak out about the organisation or its activities). In many families, the son may be expected to follow the father into the organisation, while the daughter may be expected to marry into another Mafia family, strengthening strategic alliances. The father may be more directly involved in criminal activities than the mother, but both parents tend to play a role in the transmission of crime. “The mother may sometimes justify violence, and explain why it is meaningful or important,” says Anna Sergi, a professor of criminology at the University of Essex who has analysed the impact of the removals in Calabria. In her research, Sergi cites the case of a young teenage boy who helped his father hide guns and other weapons, and, in the words of the tribunal, considered this a father-son activity, something that was “time shared with his father, part of their special relationship”. Mafia culture can also shape a child in other long-lasting ways. It may contribute, for example, to high levels of truancy and school dropout in certain parts of Italy. Nicastro points out that according to data provided in 2022, at least 21% of school-age children in Palermo have either dropped out of school or do not regularly attend lessons. “It’s very worrying,” he says. “I don’t believe such figures can be found in any other part of the Western world.” In adolescence, he says, many of these children are already taking part in criminal activities such as drug dealing. Dropping out of school can be especially harmful since teachers may be the only ones offering Mafia children a different vision, Nicastro says, pointing to the words of the 20th-Century Sicilian author Gesualdo Bufalino. “He said that you can defeat the Mafia with an army of teachers, because they can teach the values that the child wouldn’t learn from their family or from the society around them,” he says. “You need to start from early childhood.” There are also physical dangers. In 2022, there were at least 18 cases of children in Sicily being admitted to hospital for overdoses on drugs that they had found in the family home, according to local newspaper reports; one was just 13 months old . As they come of age, some people may be attracted to the certainty of the life that is set out before them, Sergi suggests – with the predetermined roles and tight-knit familial and social networks. “Looking from the outside, we may say that there is no freedom. But I would argue it’s a bit more complicated than that. It can feel like the trade-off is worth it.” They may then perpetuate the cycle with their own children. Ingrascì, whose book Gender and Organised Crime in Italy examines the role of women in the Mafia , emphasises that women who hope to escape often face the same challenges as other abuse victims. “It’s quite important to contextualise the experience of these women who are getting away from families that may be psychologically and physically abusive, because they need to be able to trust the state and they need access to women’s services,” she says. “But in Southern Italy there are few centres for female victims of violence.” She has found that many people who have grown up in the Mafia culture cannot imagine an alternative life. “They think this is normality,” she says. She recalls one interviewee who was genuinely perplexed at some of her questions, as if the family’s drug trafficking was a typical line of work. “She spoke as if I were not normal.” Those who do wish to leave may become alienated from their families who disapprove of their disloyalty. They may face threats of violence or death if there is a risk they will inform on the other members. A view of the coast of Sicily, where anti-Mafia prosecutors are trying break the cycle of organised crime (Credit: Getty Images) The freedom to choose In Italian law, a child can be separated from their family when there is strong evidence that the parents are not meeting their legal requirement to provide appropriate care and education, such that their behaviour prejudices the child’s wellbeing. Inducing a child to commit criminal acts is one such example. This was the legal basis of Liberi di Scegliere, which was established in Calabria in southern Italy by the president of the region’s youth tribunal, Judge Roberto Di Bella. “The key thing is to give these children the chance of redemption, to show them that a different life is possible,” says Giorgio De Checchi, the project’s national coordinator. In one case featured in Sergi’s research , for example, a girl in her early teens was removed from an ‘Ndrangheta family and relocated outside of Calabria. “This solution appears to be the only feasible one to avoid retaliation,” the tribunal concluded, “to save the girl from an unavoidable destiny and at the same time to allow her to experience different cultural, emotional, psychological contexts.” The tribunal hoped this would allow her to “free herself from parental conditioning”. De Checchi emphasises that each case is unique and the tribunal weighs up many factors before reaching its decisions. The tribunal may for example choose to revoke the parental authority of one parent and not the other, if one shows more willingness to reform. Sergi’s analysis of the tribunal’s judgements found that the father’s parental authority was most often revoked, whereas mothers tended to be given second chances if they were willing to offer the child a crime-free life. In all cases, the mothers were allowed to maintain some contact with the child. If there are relatives who are not part of the Mafia, the tribunal may try to place the children with them. Crucially, the children are offered psychological and educational support to steer them towards a better path in life. Dealing with critics Caramanna’s work in Palermo attempts to take a similarly careful and compassionate approach. Child-parent separation is the last resort. “Every child has the right to live in their nuclear family unless that conflicts with the right to grow up physically and psychologically healthy,” she says. In almost every case, they attempt to offer the mother the protection and security to leave with the child. “We ask these women: what do you want for your child? The alternatives are often prison or death,” says Caramanna. “If the mother refuses, we check if there’s someone trustworthy in the family circle who has distanced themselves from the criminal life,” she adds. “And before proceeding, the situation is carefully monitored by the social services and the police.” Even if the child is removed from the family home, the parents will often be granted visiting rights, provided that the child agrees to see them. And the tribunal’s decisions can be overturned, and the family reunited, if the parents sever their Mafia ties. This may sound improbable – but both programmes have seen remarkable success stories of children, and entire families, breaking free. “For any child that doesn’t choose the path we would like, there is at least another who does,” says Sergi, based on her analysis of Calabria’s youth tribunal. De Checchi points to the family of a Mafia boss who had been imprisoned for serious crimes. His son was convicted too, while the daughter was placed in foster care. It could have been a heart-breaking story, and yet the son continued to study in prison and after serving his time, decided to live an honest life, while the daughter came of age without being dragged into crime. “Even her mother decides to change her life, and to follow her children in this harrowing but necessary reconstruction process,” says De Checchi. The daughter now has a job, and the son is considering studying for law school. Even the father, who had initially opposed the court’s decision, now appreciates seeing the “rebirth” of his family, De Checchi says. “We have seen many families like this,” he adds – people who were given the chance to choose a new way of life away from crime. “Because an alternative path must always be open in any civil society worthy of that name.” * Alessia Franco is an author and a journalist focusing on history, culture, society, storytelling and its effects on people. * David Robson is a writer based in London. His most recent book is The Expectation Effect: How Your Mindset Can Transform Your Life , published in early 2022. — Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter or Instagram . If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future , Culture , Worklife , Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday. ;