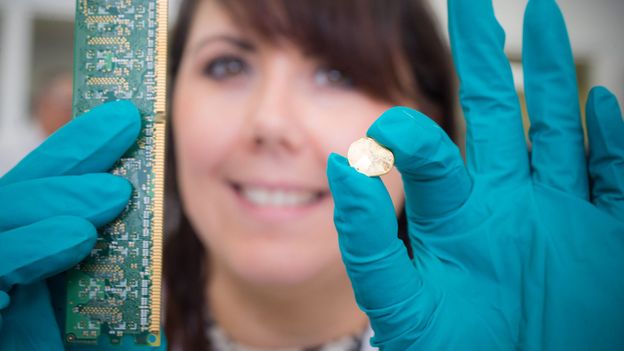

A chemical solution E-waste (also known as waste electrical and electronic equipment or WEEE) is the world’s fastest-growing waste stream . According to the United Nations Environment Programme, an estimated 50 million tonnes of e-waste is produced globally every year , weighing more than all of the commercial airliners ever made. But only 20% of that is formally recycled , and most gets thrown away and either sent to landfill or incinerated. Last year a study by price comparison service USwitch found that the UK produced the second largest amount of e-waste per person, with Norway ranking top and the US in eighth position. As demand for more portable devices and fast electronics grows, so too will the e-waste mountain. In 2019, the World Economic Forum estimated that by 2050 , annual e-waste production will more than double to 120 million tonnes. Like all critical raw materials, gold is a finite resource, yet 7% of the world’s gold is currently sitting in disused electronics . Gold extraction usually involves exporting devices to the EU or Asia where e-waste is smelted down at extremely high temperatures in a very crude and carbon-intensive process . “We want to recover as much of the precious metals as we can from things which are currently waste,” says Messenger. “Our focus is on doing this sustainably within the UK, using a process that’s effective at room temperature while producing a lot less greenhouse gas emissions than smelting.” “If we’re producing the waste, it should be our responsibility to sort it, we shouldn’t be shipping it to another country to sort it for us,” says Mark Loveridge, commercial director at the Royal Mint. He says that developing e-waste supply chains around localised recycling plants would dramatically cut the waste miles required to transport discarded electronics by sea, air and road, and the Royal Mint is already in talks with partners around the world with the ambition to globalise this technology. Swapping my lab coat for an orange hard hat, high-vis jacket and black, steel-toe-capped boots, I head to the new processing plant. Dozens of huge dumpy bags are stacked up in the far corner of this 3,000 sq m (32,292 sq ft) factory, each filled with colourful circuit boards. These have been removed from laptops and mobile phones, and delivered to the factory by a network of 50 e-waste suppliers around the country. On arrival, circuit boards are inspected and tipped into a large silver hopper which funnels this raw material into a huge multi-coloured machine. Tony Baker, director of manufacturing innovation who is overseeing the installation of this plant, explains that as circuit boards get mechanically separated and broken up, any non-gold components are kept to one side, while any gold-bearing parts such as USB ports are digitally detected and sent to a 500-litre (110 gallon) reactor. Here, the “magic green solution” gets added on a much larger scale, gold sand is extracted and, again, nuggets are produced. Because so much non-gold is removed at the start, the chemical processing is only applied to fragments containing gold, as Baker explains. The raw material used by the Royal Mint is comprised of circuit boards, rather than entire laptops or whole mobile phones. Once the gold has been extracted, the leftover non-gold components are all sent off to different parts of the supply chain for reuse, so nothing gets wasted. The gold content varies between 60 parts per million to 900 parts per million, depending on the feedstock, according to Loveridge.