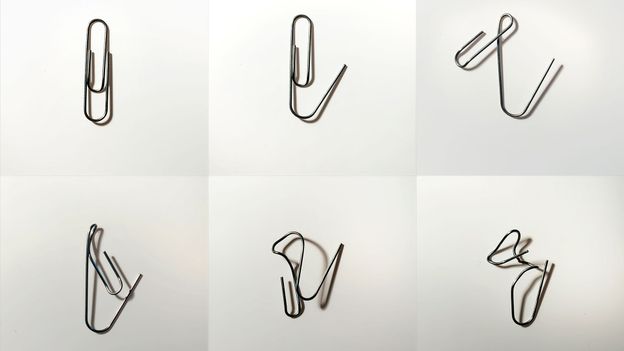

Often seen as a sign of rudeness, nerves or simply that you are not paying attention, it may be time to change our view of people who jiggle, tap and fiddle. As a child, I was regularly told off for swinging on my chair, absent-mindedly nibbling the pink rubbers off pencils and fidgeting through storytime, unable to get comfortable on the carpet while other children sat neatly cross-legged. As a result, over time, I learned to ignore the impulse to fidget. Today, I can sit still for hours with barely a shuffle. It turns out, however, I may have been better off before. Fidgeting, research is revealing, may help us maintain a healthy weight, manage stress, and possibly even live longer. “If you’re sedentary, that’s not good for you. But if you are sedentary and fidget, then actually that does reduce your risk of long-term ill health,” reveals Janet Cade, a nutritional epidemiologist at the University of Leeds, on a recent episode of the BBC’s The Infinite Monkey Cage . So let us dig into the science to find out more. Fidgeting is usually defined in dictionaries as moving or acting restlessly or nervously, but obesity expert James Levine, a professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic and president of the rare disease non-profit Fondation Ipsen, says it is better defined as a neurologically programmed rhythmic movement of a body part. He says “the fidget factor” is an outward manifestation of an innate impulse to move. Fat-fighting fidgets Worldwide, obesity has nearly tripled since 1975. Part of this is down to the increasingly sedentary nature of many forms of work . Sitting for long periods is thought to slow the metabolism, which affects the body’s ability to regulate blood sugar and blood pressure, as well as to break down body fat. But growing evidence suggests that the impulse to fidget may help us unconsciously manage our weight by prompting us to move, a little like a vibration alert on a fitness tracker. If acted upon, these tiny movements can have a big impact, says Levine. For example, Levine has found that slimmer office workers tend to act on their fidget impulses more often, standing and moving around for two hours more a day than those with obesity . This may reflect a biological predisposition to movement, he says. But fidgeting itself – even as slight as tapping a foot – may also help us to burn off excess energy, that could otherwise end up being stored as fat. One small study measuring the energy expenditure of fidgeting-like activities in 24 people found that fidgeting while sitting can increase the amount of calories burned by 29% compared to lying down without moving. Fidgeting when standing, which Levine says tends to take the form of rocking or shifting from foot to foot, boosts the number of calories burned by 38%, compared to lying down. However, while movements like fidgeting contribute to the body’s energy balance, they are not a replacement for movement or exercise. Fidgeting has often been regarded as a sign of poor manners, as this entry in the 1920s book Etiquette in Everyday Life describes (Credit: Alamy) “It’s a little like the spark plugs of a car,” says Levine, explaining the spark plugs are going when the key is in the ignition, but the car will only move if the driver presses down on the accelerator. In his analogy, the sparks are fidgets that occur no matter what, but choosing to respond to them – pushing the accelerator – unlocks benefits. In another small study, Levine examined the impact of fidgeting on human physiology by feeding 16 lean volunteers 1,000 additional calories a day over a period of eight weeks. The experiment revealed that some participants were “remarkably resilient” to fat gain because they “activated their fidget factors”. The study found overfeeding can trigger an increase energy expenditure through the fidget factor by 700 calories per day, because the participants subconsciously moved more, including walking more energetically. This “non-exercise activity thermogenesis”, as Levine and his team describe fidgeting, accounted for a 10-fold difference in fat storage. The finding is echoed in the animal kingdom. Scientists have noticed that songbirds, such as finches never seem to get fat, despite bingeing on seeds from bird feeders. This is because they unconsciously adjust how efficiently they use energy from food by changing their wingbeat frequency or singing patterns, says environmental biologist Lewis Halsey of the University of Roehampton. “We need to remember that ‘energy in’ isn’t what’s shoved down the beak but what’s taken up through the gut and then what’s extracted by the cells; looking at it as just the amount of food consumed is too simplistic,” he says. “And this goes for humans and other animals, not just songbirds.” The good news is that people who have fewer impulses to move or simply resist the urge to fidget can tap into fidgety benefits by using prompts such as a vibrating fitness tracker to move more, or simply change their routine or environment to encourage them to fidget and move, from standing while taking a phone call to planning walking meetings. Levine himself spent our 30 minute online interview standing. There could be other benefits to fidgeting that go beyond controlling our weight, though. It might also help our brains. Concentration boost There is a close relationship between movements and cognitive performance, says Maxwell Melin, a neuroscientist at the University of California Los Angeles and the California Institute of Technology’s Medical Scientist Training Program. But whether fidgeting aids concentration is not straightforward and may come down to the type of fidgeting. Fidgety people tend to daydream , which can distract them at school and work. But fidgeting, like doodling , can also provide physiological stimulation , which can help some people focus on a task . In one experiment, people who doodled throughout a phone call remembered 29% more details than those who did not, suggesting the activity may aid cognitive performance, although more research is needed. Research by Katherine Isbister, a professor of computational media at the University of California, Santa Cruz, has indicated that people often choose to fidget with objects – such as paper clips, folded pieces of paper or widgets – that provide the right level of stimulation when they need . In some cases, it can depend on the type of movement involved as to whether it is associated with good task performance, adds Melin. He gives the example of a professional tennis player bouncing a ball before serving. “They do not need to bounce the ball for a serve, but many professionals find a pre-serve routine helps them focus,” he says. However, swatting a fly before hitting a serve would be an example of a non-stereotyped movement. In other words, some actions can sharpen our focus, while other movements that are unrelated to completing a task seem to distract us. “What we still don’t know is the directionality of this relationship,” says Melin. “Do stereotyped movements actually cause better task performance, or are they merely a symptom of a person who is actively engaged in the task at hand?” Melin is intrigued by whether movements have a causal impact on sophisticated thinking skills, because they could potentially be used to help people with ADHD, who can be prone to fidgeting, and other conditions that affect behaviour. A longer life? While there is no evidence to show that fidgeting directly leads to a longer life, experts know that chronic stress can shorten our lifespan, while a sedentary lifestyle increases all causes of mortality , doubling the risk of cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and obesity, as well as increasing the risks of depression and anxiety. Fidgeting may help with both. For one, fidgeting may help us cope with stress. In one study, 42 men were put in a stressful situation , given a simulated job interview followed by a mental arithmetic task that they had to complete in front of two people. Researchers found that those who fidgeted by displaying “displacement behaviours” such as scratching, biting their lips or touching their face found the experience less stressful. Why humans evolved to be lazier than our ancestors Meanwhile, fidgeting also may help lower some of the other risks that come with a sedentary lifestyle. Researchers have found that feet tapping while sitting, for example, can protect the arteries in legs and potentially help prevent arterial disease . Meanwhile, drawing upon the UK Women’s Cohort Study , which analyses the eating patterns of more than 35,000 women, researchers found no increased risk of mortality from longer sitting times in those who considered themselves to fidget a moderate amount or a lot when compared to more active women. The findings raise questions about whether the way we perceive people who fidget should change , says Cade. Fidgeting is often seen as rude or an indication that someone is not concentrating. But it these simple movements are beneficial for our health, maybe they should be indulged, she says. They also support the suggestion that it is best to avoid sitting still for long periods of time and fidgeting may offer enough of a break to make a difference. Levine believes that crushing the natural urge to fidget is ” a public health calamity ” but society has an opportunity to fight against sedentary routines and environments. “If you allow the body’s natural drive to move… the likelihood is you are actually going to be healthier, happier and thinner, and quite frankly, live longer,” he says. — Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook , or follow us on Twitter or Instagram . If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called “The Essential List” – a handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future , Culture , Worklife , Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday. ;