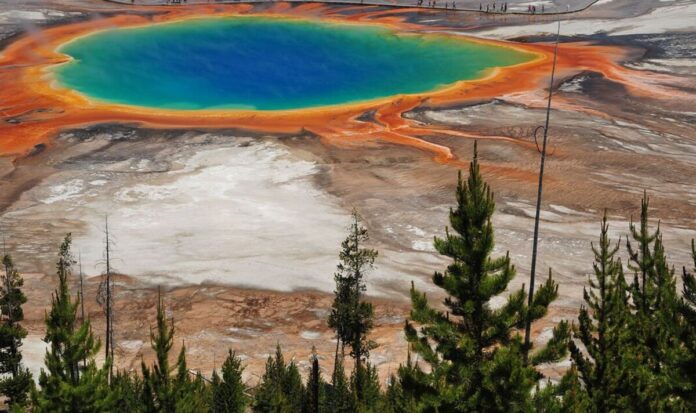

When all is stripped back, it’s a wonder that humans are still alive. The planet is filled with danger, threats seemingly around every corner, much of it completely unavoidable or unpredictable. Well, sort of. For hundreds of thousands of years, humans have largely lived peacefully alongside the things that pose the greatest dangers: wild beasts, freak weather, supervolcanoes , asteroid impacts. More recently, new existential risks have come into focus, things like the effects of climate change and the lingering anxiety of all-out nuclear warfare . But what exactly poses the greatest threat? And is humanity really at risk from a single thing? Express.co.uk spoke to three experts about some of the most pressing dangers to humanity of our time – some avoidable, others entirely out of our control. A man protests about nuclear weapons during the Cold War, in 1979 (Image: GETTY) In the grand scheme of things, nuclear warfare is the baby of existential threat, having only been around since the mid-20th century . But this doesn’t mean it is the one to stress less about – far from it. The threat of nuclear oblivion is one of if not the most talked about threats to existence, with Russia ‘s invasion of Ukraine only reigniting what many believed was a menace no more. “Today, it’s a plausible route to the end of humanity,” said Julian Lindley-French , Chairman of The Alphen Group (TAG) who has worked with NATO and penned numerous books on defence strategy. He noted that once countries start using them, an increasingly likely scenario in today’s world, “you cross a very, very big line” which can quickly lead to “escalation”. The 21st century has seen the democratisation of ownership of nuclear weapons. No longer is it a case where the so-called Big Powers hold sway over the potentially world-ending devices. Countries like North Korea and Pakistan now possess a considerable number of missiles with nuclear capabilities, while reactive powers like Iran look to hone their skills in building them. Little Boy being dropped on Hiroshima, in 1945, the world’s first nuclear strike (Image: GETTY) For Mr Lindley-French, this poses the greatest risk: that localised and regional nuclear warfare could well make swathes of the world uninhabitable. “You could certainly see a situation in which a pair of regional powers go to war – Iran and Israel, India and Pakistan – and exchange nuclear weapons,” he said. Mr Lindley-French did not rule out the chances of a global catastrophe, acknowledging that “these wars could suck in bigger powers, and the biggest strike in all of this is still a major salvo exchange between those great powers”. He continued: “That would probably lead to at least a hemispheric extinction because of a nuclear winter that may last for as long as five years, would kill crops and everything else. “It would truly be a global war, a third World War, and would almost certainly lead to the extinction of a major part of the global population.” Countries like North Korea now have advanced nuclear capabilities (Image: GETTY) There are volcanoes, and then there are supervolcanoes : great hulks of structures that erupt at least a thousand times more material than ordinary large volcanoes. After eruptions, supervolcanoes form big depressions in the ground called calderas which hide vast lakes of magma that could, in theory, blow at any moment. There are about 20 supervolcanoes peppered across the planet, the most notable ones being Lake Toba in Indonesia , Lake Taupo in New Zealand, Campi Flegrei in Italy, and Yellowstone in the US. These are regions filled with those calderas, not just one but many points from which supereruptions could occur. Generally speaking, they erupt around once every 10,0000 years, “and there’s no reason to believe there won’t be a super eruption in the future,” said Professor Christopher Kilburn, a volcanologist at University College London (UCL). The most recent supervolcano eruption occurred at Taupo around 27,000 years ago and would’ve caused untold destruction. Some eruptions, like that at Toba, are said to have had far-reaching effects, causing severe global winters and squeezing the world’s population size. But what would an eruption do to today’s world? “Well, the immediate vicinity of the supereruption would be completely devastated,” Prof Kilburn said. The iconic Grand Prismatic Spring, one of the many signs of volcanic activity beneath Yellowstone (Image: GETTY) “A global effect, that’s a different story. Clouds of fine volcanic ash will rise into the stratosphere and will block sunlight for maybe several years. “More important is the release of volcanic gasses like sulphur dioxide, which form opaque droplets of sulphuric acid and reduce the amount of sunlight but for much longer than the ash. “It would cause a total disruption of the global food supply; depending on where the eruption occurs it will have major knock-on effects. “If it happens at Yellowstone that would have the possibility to overwhelm the global economy because the world’s leading economy will be brought to its knees. “Many economic repercussions would follow which would then disrupt trade, food supplies, general activities around the world and that in turn may lead to other destabilising effects.” These effects may not wipe the entire human race out but they would have a significant impact on the number of people who survived. Crucially, he said, is how we might recover from any such eruption. It could set humans back hundreds of years. For now, there is no evidence that a super eruption will happen any time soon. But Prof Kilburn warns that many volcanoes, including supervolcanoes, aren’t actively being monitored every day. “It’s a myth that the world is properly observing monitors – they measure particular points every few months, but even then, they may not have the measurements relevant to understanding if there’s going to be a building up to a large scale eruption.” Lake Toba in Indonesia hides one of the world’s largest supervolcano calderas (Image: GETTY) In August 2022, an alarming analysis paper was published, warning that the risk of global societal collapse or human extinction has been “dangerously underexplored”. Scientists today attribute many of the freak weather events to the slow-burning effects of climate change: an unprecedented heatwave in Europe, devastating wildfires in Hawaii, droughts in Africa. Dr Luke Kemp at the University of Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, who led the analysis, told Express.co.uk that while climate change does pose a significant threat to humans, what it contains is a series of risks that are far-reaching and possibly far more dangerous than rising temperatures in itself. It is all about knock-on effects and strings of disasters that lead into one another and end in what could be total destruction. He gives an example from 2010 in which a cascade effect can clearly be seen. “Back then, an Arctic warming drive heatwave hit Russia , and sharply decreased crop yields,” he said. “Russian responded by imposing a grain export ban which in turn led to a spike in global grain prices. “This hike in prices contributed to unrest and political change in Egypt, and correlated with a surge in food bank usage in the UK of roughly 50 percent.” Heatwaves are only one in a string of potential outcomes of climate change (Image: GETTY) The world is deeply connected, he said, with slight change somewhere as far away as Siberia making itself known in Africa or further afield. “This is what we’re talking about when we talk about the risks,” Dr Kemp said. “Militia groups fighting in Africa because of things related to raising temperatures could lead to state failure, which in turn could potentially impact the cost of particular resource links in our country, which in turn has ripple effects throughout the global economy.” It can manifest itself in many different ways. The civil war in Syria led to a mass displacement of people desperate to flee conflict and persecution, which had a knock-on effect on European politics in the following years. Since the paper was released, on the climate front at least, have governments woken up to the potential risks climate change poses on humanity? “I would say not,” Dr Kemp said. “Currently, we still have most things based on mitigation and planning on integrated assessment models which aren’t effective ways of exploring the worst-case scenarios. “While our paper gained a lot of attention and traction, as far as I can see, it’s not led to governments doing that worst-case scenario planning. We can only hope that changes.”