With short, dirty blonde hair teased into a bouffant, a silk scarf knotted around her neck and jaunty gold accessories, Brigid Berlin steals the show in Chelsea Girls, Andy Warhol’s cult 1966 split-screen film. Her character, the Duchess, was a louche amphetamine dealer holed up in a room at the eponymous residential hotel. The character’s nickname was fitting for Berlin. The daughter of the president then of the Hearst Corporation, the influential publishing company, and his socialite wife, Honey, Berlin had rebelled against her Upper East Side upbringing and gravitated towards the downtown scene. Also fitting was the character itself. Berlin had been a prodigious user of amphetamines since childhood, when her mother had encouraged their use so that Berlin would lose weight.

Berlin had joined Warhol’s Silver Factory (his first) in 1964 and remained, in one role or another, associated with the artist until his death in 1987. The pair were close – often described as best friends – and alike in many ways. Theirs was a symbiotic relationship, feeding off the other’s personality and creativity. Both Berlin and Warhol worried about their weight – their own and that of the other. “Brigid called and said she’s down to 197. Ever since she saw herself in Bad [a film, produced by Warhol released in 1977] weighing 300 pounds and went on a diet, she’s so boring to talk to,” Warhol recorded in his daily audio diary on November 28, 1976. Each had issues with addiction – to drugs, to drink and to different kinds of foods. They even both suffered from gallbladder disease, with Berlin having hers successfully removed some months before Warhol’s own operation, which would indirectly result in his death.

But more than just a Warhol acolyte, Berlin was an artist in her own right – and a true original. Brigid Berlin: The Heaviest, a new exhibition at the Vito Schnabel gallery in New York (until August 18), is the first to explore all aspects of her life and art. Curated by Alison M Gingeras, the exhibition’s setting is inspired by the interior of her final apartment. Some of the gallery’s walls are covered in the same bespoke floral wallpaper from the US manufacturer Twigs that featured in Berlin’s home, and the exhibition includes never before seen family photographs, letters and memorabilia. Another of the exhibition’s wall coverings turns attention to Berlin’s creative output, in the form of a newly commissioned wallpaper featuring J-cards from her extensive audio archive. Both Warhol and Berlin were obsessed with documenting every aspect of their daily lives and, importantly, the people they met, using Polaroids and cassette recordings. While Warhol would become well known for this practice, it was Berlin’s use of both media that prompted him to take them up. This was not uncharacteristic of Warhol. He took constant creative inspiration from others, both in his own circle and further afield, channelling his borrowings and making them icons of his own practice.

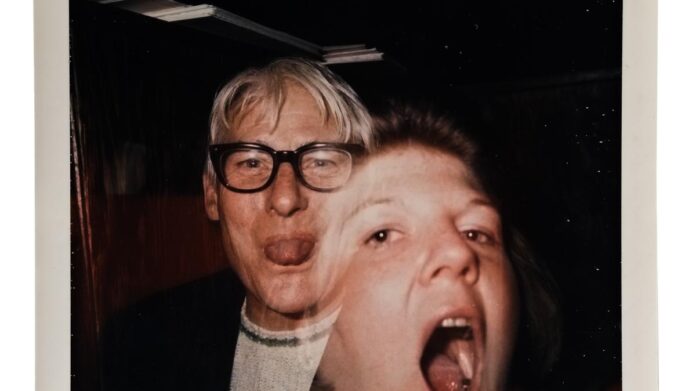

In 1970, Polaroids and audio cassettes featured in Berlin’s first solo show, at the Heiner Friedrich Gallery in Cologne, Germany. Brigid Berlin: The Heaviest presents the first opportunity in 50 years to experience her audio recordings. Amounting to almost a thousand hours, these date principally from 1969-74 and feature monologues, fights with her parents, daily calls with Andy Warhol and conversations with artists, who were Berlin’s bread and butter. “Artists excite me. Every time I meet a new one, I’m thrilled that I know one more!” she once explained. Much of the exhibition underscores her interactions with a veritable who’s who of the biggest names in the art world of the 1960s and early 1970s, including Richard Serra, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Aside from immortalising these artists’ thoughts on tape, Berlin captured them, as well as people she met in Warhol’s orbit (such as the Vogue editor Diana Vreeland), with her Polaroid camera. She neatly organised the resulting images in leather-bound books, each with a different theme. Berlin also used the Polaroid camera in much the same way most of us use our phone cameras today. She was a pioneer of the selfie, except Berlin’s selfies experimented with double exposure to superimpose her image on to a snapshot of another person. In one, Willem de Kooning, the abstract expressionist, jauntily sticks out his tongue for Berlin’s camera while a ghostly imprint of Berlin’s face hovers in front of him.

Aside from her encounters with legends of the art world, the exhibition spotlights Berlin’s other creative outputs. She was an artist who worked across media, not just photography. Perhaps symptomatic of her lifelong battle with her weight, Berlin also used her body to make art, including paintings dubbed “Tit Prints”. In later life she produced a series of tongue-in-cheek needlepoint creations, including some based on covers of the New York Post, as well as performance art.