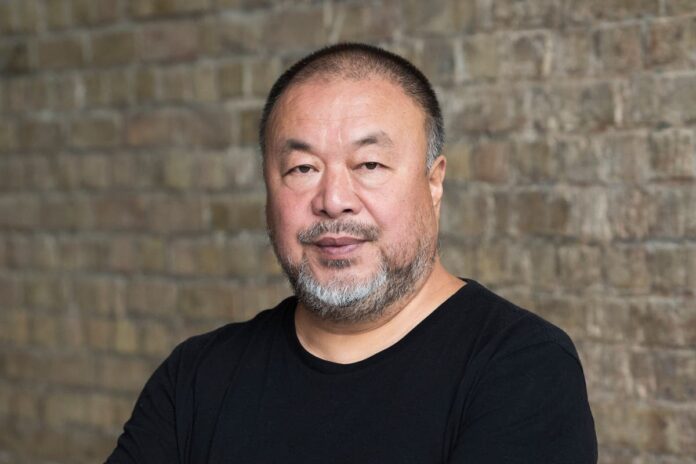

Visual artist Ai Weiwei says censorship in his homeland of China is ‘suffocating’ creativity. Ai’s work is all about speaking truth to power. This includes the Remembering, an installation dedicated to those who lost their lives in the Sichuan earthquake in 2008; and filling the Tate Modern’s main hall with millions of hand-crafted porcelain sunflower seeds in 2010 – often interpreted as a symbol of how the people of China are able to stand up against the ruling Communist Party. An outspoken critic of Chinese authorities, he was arrested at Beijing Capital International Airport in 2011 and detained for 81 days. In 2015 he left China for the last time, and is now based in Lisbon, Portugal. Living abroad, Ai is free to express himself – something he knows isn’t possible for artists in his homeland. ‘Censorship certainly destroys a new voice,’ Ai says. ‘ Freedom of expression is the force of creativity. For the authorities, maintaining stability is much more important than so-called creativity.’ The 65-year-old suggests those in power ‘sacrifice’ creativity for order – and he keenly feels the effects of this. ‘It’s suffocating – you don’t have fresh air, and it’s hard to breathe.’ Ai’s work addresses political and social issues in China, and he says this approach is ‘important, [but] also not important when you have a society where honest, frank language has been forbidden, and [there is] strong censorship’. He suggests censorship limits language, meaning writers are less able to express their interior thoughts and feelings. However, one writer who was able to do this was Wang Xiaobo, a Chinese novelist who died in 1997 at the age of 44. According to Ai, Wang is still the country’s most popular writer – and his work has never been taken off the shelves in China. ‘You can still buy it in bookstores,’ Ai reflects. ‘My writing you certainly can’t – it’s not online or in stores.’ Wang’s work has recently been published in English for the first time – his book of essays called Pleasure Of Thinking, and Golden Age , a satirical novel about life as an ‘educated youth’ in the Cultural Revolution. This was a 10 year period from 1966 where leader Mao Zedong purged capitalistic and traditional elements from Chinese society, and ‘educated youths’ were young people sent to work in the countryside. Discussing Golden Age, Ai says: ‘Normally you don’t read things like that. It’s a very personal narrative about erotic moments’, which was very surprising in ‘a very restricted society like the Cultural Revolution’. He continues: ‘It’s very unique because the whole generation was being forced to not review [their] inner feelings – that could be considered a dangerous act.’ For Ai, Wang’s strength comes from his ability to write about his inner thoughts and emotions. In a ‘society like China’, he says, ‘You cannot really calmly expose yourself very often. Very often, even among writers, they don’t have this kind of graceful style under the language [as Wang]… His writing is so honest.’ While you can still read Wang’s work in China today, Ai suggests if he was living and working today, he would likely be censored because his style is still ‘very, very subversive’. Golden Age isn’t an outright critique of the Cultural Revolution, but darkness is lurking underneath the humour. Ai suggests you can ‘sense’ the reality of what is happening – Wang himself was an educated youth for two years, so the book can be seen as semi-autobiographical – and he successfully shows ‘the mental condition of that time’. In recent years, under the strict censorship of China, one blog writer who caught Ai’s attention – who saw similarities with Wang’s work. But this was ‘only for a few years online, then suddenly his voice disappeared… [He was] a very popular blog writer – probably the most popular one, but [he] suddenly disappeared [from the internet], because I guess it became too dangerous.’ With the new publications, Western audiences will be able to read Wang’s work in full for the first time – and Ai wants readers ‘to see China still has these very liberal and very intelligent writers, but they’re just under this heavy political control. They cannot be introduced, or cannot even be published.’ Golden Age and Pleasure Of Thinking by Wang Xiaobo, translated by Yan Yan, are published by Penguin Classics.