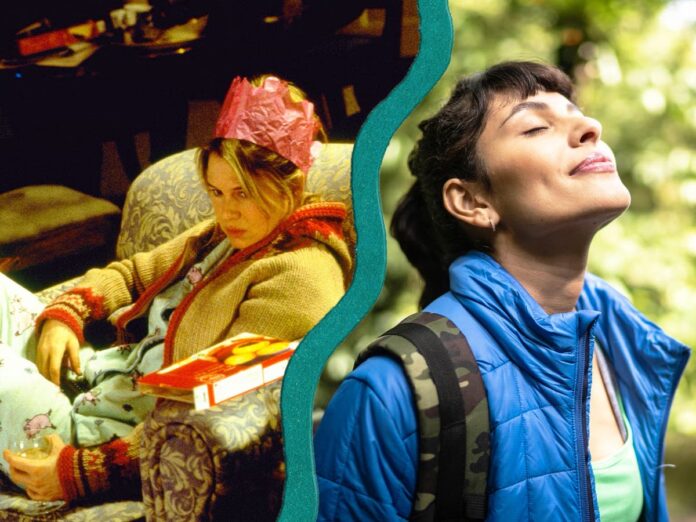

I was a teenager in the early Noughties, so my cultural emblem for female solitude was Renee Zellweger’s Bridget Jones , drinking wine in button-down flannel pyjamas to the opening verse of ‘All By Myself’. As she checks her answerphone – ‘You have no messages’ – and drains her glass, we’re left in no doubt that this famous, tragicomic scene is one of loneliness and isolation, rather than aspirational glamour (despite her covetable position of living alone in a central London flat aged 32). Two decades later, things couldn’t look more different. This summer, a Vogue travel feature declared solitude a ‘coveted commodity’. Hermit , a new solitude-inspired memoir by Jade Angeles Fitton – a journalist in her mid-thirties – is a trending summer read, while Lady Gaga recently declared her desire for a ‘life of solitude’. The hashtag #solodate also has over 282 million views on TikTok. Suffice to say, solitude has transformed from a shameful habitat for a self-proclaimed ‘spinster’ like Bridget Jones into a boast-worthy status symbol. It’s sparked a female-led solo travel boom, too: 84 per cent of solo travellers are women, according to data by Booking.com , a figure no doubt inspired, in part, by the 2010 film adaptation of Elizabeth Gilbert’s self-discovery yarn Eat Pray Love . And in 2019, OpenTable reported a rise in restaurant bookings for one (up 160 per cent over a four-year period) – a far cry from Lindsay Lohan’s socially outcast character in Mean Girls retreating to a bathroom stall with her lunch tray to avoid eating alone in the cafeteria. Through my own work, as the author and podcaster behind Alonement , I’ve witnessed my predominantly female, millennial audience connect with this topic – regularly sharing and hash-tagging their own #alonement (a word I invented to describe positive alone time) on social media. ‘Soloism’ (as Quartz dubbed this trend in 2019) is broadly defined as ‘people making active choices to live, work, entertain, and parent by themselves’. It could be taking yourself out for dinner; it could be travelling the world alone. While men and women might (and do) indulge in these activities, sociologist Jack Fong observes that there’s a ‘gendered dimension’ to solitude. ‘Men who write about [it], like Nietzsche, tend to go out to the forest or desert, to find a philosophical basis for their existential crisis. Meanwhile, women employ solitude to get in touch with their emotional selves, and express their identity to the fullest degree. It’s an emancipation from the cultural prescription of how a woman has historically been told to behave within a patriarchal society, creating a nest for future offspring.’ Bella Brown, 34, is a senior manager working in tech who lives with a flatmate in Clapham, and she tells me: ‘Solitude creates a delicious opportunity to become self-aware – my biggest goal in life. I travel alone at least once a year; go for solo date nights at my favourite restaurant; visit museums when I want to immerse myself without interference from someone else. The time I spend with friends becomes more rewarding because it’s an intentional choice.’

Solitude used to mean sad singledom. Now it’s become a status symbol

Sourceindependent.co.uk

RELATED ARTICLES