After decades of work and countless setbacks, researchers believe this shot is the best yet to fight the disease – critics aren’t convinced

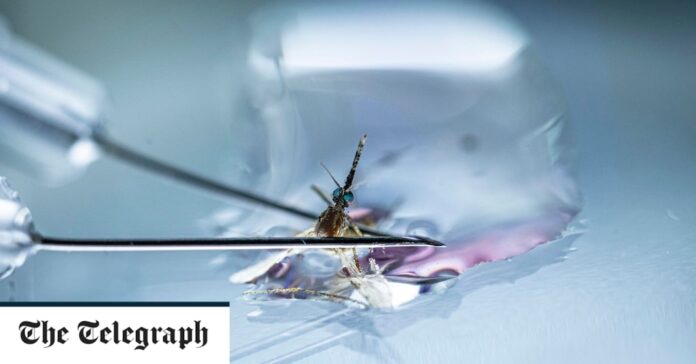

The severed head of the mosquito loomed large under the lens of the microscope. At a nondescript lab on the outskirts of Oxford, scientists were dissecting the tiny insects to reach the malaria-carrying parasites lurking inside.

“We just gently pull the head off, and hopefully the salivary gland – where the parasite lives – comes with it,” said Prof Katie Ewer, a professor of vaccine immunology at the Jenner Institute, pointing at the eyelash-shaped gland on the glass slide.

Over the following 48 hours the minuscule parasites extracted faced a new adversary: vials of blood gathered from the participants of a malaria vaccine trial in Kenya.

The experiment – which aimed to test the antibody response triggered by the vaccine, known as R21 – was yet another piece of data the Oxford academics were pulling together ahead of a critical deadline.