When novelist Stefan Hertmans learnt his home once belonged to ‘a Jew-hunter for the Waffen-SS’, he dug deeper – and discovered a grim story

Stefan Hertmans is an elder statesman of Flemish literature – a poet, novelist, short story writer and academic. Only a handful of his books have been translated into English, including the novel War and Turpentine, which was longlisted for the Man Booker International prize in 2017. If, like me – to my shame – you know little about Flemish literature, The Ascent would be a pretty good place to start. It is a crash-course in 20th-century Flemish history and culture. Prepare to descend.

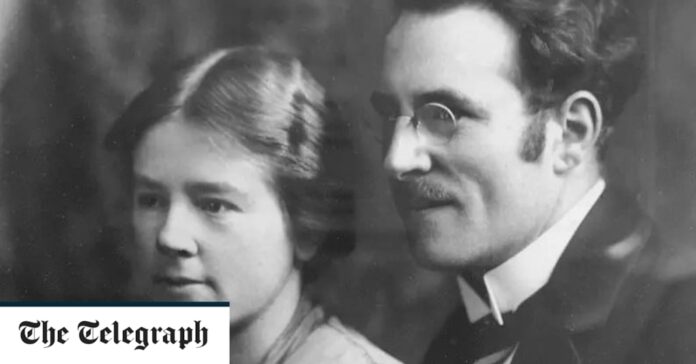

Based on years of research and augmented with personal reflections and fictional episodes and illustrated with rather elliptical and mournful black-and-white photographs, the book tells the true story of Willem Verhulst, a Flemish nationalist from Ghent who became a “confidential agent”, a Vertrauensmann or V-Mann, or what Hertmans simply calls “a Jew-hunter for the Waffen-SS”. It turns out that Hertmans had ended up buying the beautiful old Verhulst family home, “for a sum that would not even buy me a mid-size car today”.

Hertmans brilliantly describes and imagines scenes in the house. He interviews various surviving Verhulst family members, and takes particular issue with the account of Willem’s life in a book by his son, a famous Flemish professor of history, Adriaan Verhulst. So, it’s a story about a family, a primer on the history of collaboration with the Nazis during the war, and a book about a house. But at the centre of it all is Willem Verhulst.

Willem is a sad, pathetic creature, almost too good – that is, too awful – to be true. Blind in one eye – a “Flemish cyclops”, according to Hertmans – Willem comes across in his quoted letters and diaries as a weak, vain and foolish man, though also half-conscious of his many sins. “In any case […] what I should have seen, I did not see; but I also saw many things I’d have been better off not seeing, and pretending I hadn’t seen a thing was often useful in later life, a habit that was difficult to break.” He becomes an enthusiastic Nazi, founding something called the Comite voor Dietsche Actie, whose grand aim is the unity of all Dutch-speaking peoples in a fascist Greater Netherlands. In reality, most of his time is spent filing reports to send Jews, communists and Boy Scout leaders to their deaths.