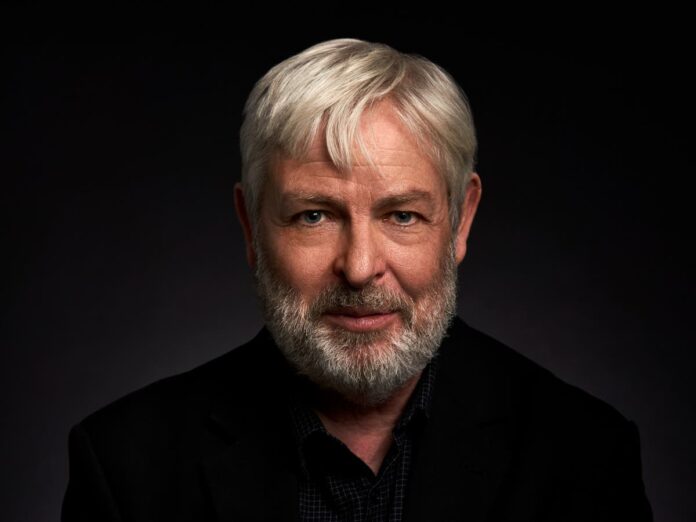

Jonathan Coe can thank the government’s recent instability for making him (ever so slightly) late to our interview. ‘Sorry, I’ve spent all afternoon writing an article for [the Spanish newspaper] El Pais about the Conservative Party chaos of the last few weeks,’ he explains, with scrupulous politeness. The novelist’s frown suggests that the process has been anything but therapeutic. ‘Er, no, hardly.’ Taxing though it may have been, the newspaper was right to seek his thoughts. Ever since his 1994 breakthrough novel, What A Carve Up!, a biting socio-political comedy and deadly critique of Tory rule under Margaret Thatcher and John Major, Coe has established himself as one of our finest writers. He’s also one of the very best at nailing the British character – rather than caricaturing it – on the page. He’s written all sorts of novels – his most recent, 2020’s Mr Wilder and Me, recounted the autumn years of the legendary Hollywood director Billy Wilder – but has been most celebrated for his state of the nation books, among them 2015’s Number 11, and his 2018 Costa-winning Middle England, both of which also looked at politics and power, and then duly satirised both. For his new novel, Bournville, he has returned his gaze to headline issues because, frankly, how could he not? In an era where rolling BBC News is more compelling than anything Netflix could dream up, Coe felt almost duty-bound to record it. The book spans several generations of the Lamb family from Birmingham – specifically the enclave of Bournville, home to the Cadbury chocolate factory. Geoffrey is a classicist, Mary a PE teacher. Along with their three sons, they might be described as a quintessential British type: taciturn, buttoned up, formal, polite. Each chapter occurs at a moment of national significance experienced through the prism of its television coverage: the 1966 World Cup final, the marriage of Charles and Diana in 1981, Diana’s death in 1997. Across the years, Coe paints a vivid social history of post-war Britain. This is a country slowly but surely evolving – and not always willingly. It becomes more multicultural, more reliant upon its European neighbours, and watches as its Empire steadily crumbles. Change is good, yes, but change also discombobulates.It’s easy, then, to see why foreign newspapers might call upon him to decipher the chaos of Britain today. And so what did he tell El Pais? Coughing into his fist, he says, ‘Well, as I’m sure you know, there’s never one single answer to these questions, but I do think it has a lot to do with the 1980s, and Thatcher, the running down of our manufacturing sector and the building up of our financial sector, the decision to stop being one of the workshops of the world and to become instead one of the banks of the world. And of course, this really came home to roost in 2008,’ he stresses, ‘with the financial crisis, and then more recently with Brexit.’ As the decades unfold in Bournville, the impact of immigration is felt by the Lambs. Indian families move to the town. One of Mary’s sons marries a Black woman. At Cadbury itself, meanwhile, there are developing problems. Europe refuses to import its chocolate because it’s not considered ‘proper’ chocolate; they think it ‘too greasy’. (The reader may well find themselves agreeing with Europe on this.) Coe impishly posits that this might be at least one reason why ‘we’ began to distrust – and even dislike – our European neighbours, to the extent that, in 2016, we divorced them. ‘Brexit was all about reassessing our independence, but we eventually became a very dependent country, didn’t we?’ he laments. In the hands of another author, Bournville might have been an angry book. And while it’s true that Boris Johnson gets an unflattering cameo, and the monarchy gets even shorter shrift (one character describes them as ‘bloated parasites, feasting on the putrid corpse of a broken social system’), the novel is mostly quiet, earnest, contemplative. At one point, Mary’s son Martin is summed up thus: ‘If he had a credo, it was moderation in all things.’ Later, when Martin worries he might be dull, his wife reassures him, ‘I’ve never met anyone so deliciously sensible.’ By the 1980s, in a feat of unusual daring, he joins the SDP. It’s only towards its final chapters that the book builds up a righteous sense of ire. Mary’s demise is a lonely one – an echo of the death of Coe’s own mother. She died of an aneurysm during the pandemic, the family unable to be with her during her final hours due to lockdown restrictions.In endeavouring to explain its largely gentle tone, Coe says, ‘Well, that’s partly me, and the way my family were. We were never the sort to raise our voices with each other. Even when there were disagreements, people would just go into the other room and sit and fume and get over it. There were a lot of conversations not had. But then I think a lot of families are like that, although maybe less these days. But in the 1950s and 60s, that’s how things were done,’ he says. ‘I mean, personally, I am angry – very angry – about Brexit, and about the terrible inequalities we face, the indifference in the face of climate change. But as a writer, I worry about writing partisan books. I don’t think books should be polemical. I’ve done that in the past, particularly with What A Carve Up!, but that book kept running up against a lot of readers who didn’t like its politics. I’d much rather readers disliked my books for artistic or aesthetic reasons than political ones.’ Coe’s latest book ‘Bournville’He pauses to consider this further, and looks off into the distance. My dictaphone records 11 seconds of silence. ‘To me, Bournville is a very emotional book, perhaps overly emotional, certainly towards the end, but anger isn’t one of the emotions I write from. I think anger in literature is far more powerful if it remains between the lines, if the reader intuits, rather than has it thrown in their face.’ Coe says that he wouldn’t have been able to write Bournville had his mother been alive. ‘She would have found it too painful,’ he says. ‘She was very private.’ Neither of his parents were big readers, and his entire family – his brother works in sales – was slightly puzzled by the career he chose for himself. ‘They were more readers of genre fiction, my parents, and so what I wrote was outside their normal reading experience. My father, who died nine years ago, did read my first three books, but obviously didn’t like them. When he read my fourth [What A Carve Up!], he said, ‘Oh, this is much better, you’re getting somewhere now.’ Which was a surprise, as he had always been very Conservative in his politics. He gave me a copy of Kane and Abel by Jeffrey Archer, and said, ‘I think you should read this now.’ Archer was his favourite author.’ He purses his lips, an almost-smile. ‘Each to their own.’ Coe had always wanted to write. He started dabbling in his early teens, and was first published at 26. He’s done nothing else since. ‘I’ve been very fortunate because I’ve never had to support myself by, say, teaching,’ the 61-year-old says. ‘But then the key to that has been translations, and having bigger audiences in France and Italy than I do here.’ He is so revered in Italy that he was recently approached by a jazz act called Artchipel Orchestra, who wanted to revive some songs he wrote years ago – in his spare time, Coe likes to dabble in music – and they’ve asked him to perform with them in Milan in December, the writer on keyboards. In France, he has won the prestigious Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger award. ‘Without those royalties [from overseas book sales], I simply wouldn’t be able to survive.’ When he does book tours around Europe, he often finds himself cast in the role of British diplomat, his readers wanting him – like El Pais did – to explain the eccentricities of his country to them. ‘I don’t apologise, because it’s not for me to do that, though I do try to explain,’ he says. But surely the writer in him must take at least some glee from our ongoing political flux? After all, many of his books have taken advantage of governmental upheaval. And social instability always works wonders for plots, no? He frowns again, a pronounced ‘V’-shape sprouting between the eyebrows. ‘No, no. No. I would really rather not live in interesting times, thank you. I’d much prefer boring times, because I’d still find something to write about. In fact,’ he says, ‘I’d quite happily throw away my entire canon for a slightly more stable, slightly more just Britain.’ ‘Bournville’ by Jonathan Coe is out now

Jonathan Coe: ‘I would really rather not live in interesting times, thank you’

Sourceindependent.co.uk

RELATED ARTICLES